Excerpted from the author’s 2021 honors thesis

Jia Zhangke’s Emotional Questioning of Contemporary China

Tyler Kwok

Tao (Zhao Tao), a performer at Beijing World Park, moves solo through an uncertain and shifting Chinese cultural landscape

China’s tumultuous 20th century history is marked by sweeping political movements — the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution — that mobilized millions of Chinese citizens under the banners of nationalism and communism. These periods have been central to the meditations of many films, like Zhang Yimou’s To Live (1994) and Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine (1993), which reveal the upheaval of their times through grand, dramatic narratives. The 1990s are another unique but equally significant era in China’s modern history because of the country’s transition away from a communist state and movement towards a capitalistic economy; however, China’s embracement of capitalism — a step in the right direction to many Western perspectives — can overshadow the many hardships caused by this transformative decade. This essay will uncover the transforming social, political, and cultural context of China in the 1990s that gave rise to several trends (like, urban filmmaking, independent filmmaking, and observational documentary) that serve as the foundation for one of China’s most renowned filmmakers, Jia Zhangke. Then, through a comparative analysis of two of his works, The World (2004) and Still Life (2006), I will demonstrate how he questions major contradictions in Chinese society and uses local settings to critique forces of globalization.

Era of Transformation

After Mao’s death, China experienced a void in leadership while facing the aftermath of his politics. Throughout the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Chinese citizens starved as the economy was in shambles (Opening the Door). People began feeling increasingly disillusioned with Maoism that had dominated all walks of life for decades, including Deng Xiaoping, a resilient politician who had personally endured the cruelty brought on by the Cultural Revolution. He realized China’s dire need for reform and sought to introduce the country into the global market economy. Deng advocated for privatization and harked on the prospect of personal wealth as his major selling point, principles that directly opposed Mao’s embrace of collectivity and condemnation of consumerism. After he garnered enough public support, Deng set the stage for the country’s era of transformation.

Deng opened China’s doors to foreign investment and developed several cities into Special Economic Zones that were dedicated to free enterprise. Before long, a country that had so adamantly supported Mao’s form of communism was looking more and more capitalistic. Subsequently, Chinese consumerism exploded as the excitement of buying a color TV, a radio, or the latest fashion took hold of the country. On the surface, China was successfully combining a socialist society with capitalist policies and prospering as a result. In an interview during his first U.S. visit, Deng assured his sceptics, “To get rich is not a sin …. Wealth in a socialist country belongs to the people. That’s why our policy won’t lead to a situation where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer” (quoted in Opening the Door). However, the theorizing behind this line of thought was, according to Orville Schell, “riddled with contractions” (quoted in Opening the Door). Behind the façade of prosperity was a mounting inequality as groups were left behind the growth and opportunity brought on by economic reform.

Cities were the most visible sites of transformation because of their rapidly changing skylines and seemingly overnight intake of millions of new residents. Initially, they signaled social mobility and the promise of earning a higher income. Huge numbers of rural workers flooded to cities in search of work to support their families back home. In just a four-year span between 1989 and 1993, the number of migrant workers nationwide increased from 30 million to 62 million (Li 4). This massive relocation of people is significant because, first, it provided the labor for China to rapidly develop and restructure its cities to accommodate a market economy. With so much cheap labor, developers could very quickly tear down old buildings to raise skyscrapers and factories in their place. Second, it created a surplus of workers and overpopulation that presented a host of problems. With so many workers to choose from, employers could subject these migrant workers to dangerous working conditions, unreasonable hours, and low wages knowing there would always be someone else willing to take their place should a worker object. Moreover, every Chinese citizen possesses a household registration (hukou) that classifies them as either rural or urban residents. Not only does a rural registration afford one fewer rights and privileges while in the city, it is also nearly impossible to change a rural card to an urban one, meaning the masses of migrant workers occupying much of China’s cities were an inherently marginalized group.

“Chai-na,” translating to the act of “tearing down,” is truly a fitting name to describe contemporary China as the country experienced massive restructuring (Lu 137). Chai quickly became a central theme in China’s visual culture not just from the changes in cityscapes, but also as a “symbolic and psychological destruction of the social and fabric of families and neighborhoods” (Lu 138). Filmmakers and other artists began paying closer attention to the impact that massive global forces had on individuals. Jia describes his Urban Generation of filmmakers as “the generation that finally escaped from the collective life … we really value the individual reaction to the daily, historical and political changes in China … this kind of individualism is the rebellion to the last several decades of the collective sense in Communist Party arts” (Interview with Jia Zhangke). Their filmmaking lends itself to tell the stories of marginalized experiences, exploring the ways in which migrant workers, artists, or petty criminals struggle to carve out their place in an ever-changing country.

Amidst the reform, digital video technology emerged in the country and sparked a revolution of amateur filmmakers. The cheaper costs and greater accessibility of digital video recorders enabled anyone inspired to make a film to do so, giving rise to the “age of the amateur” as Jia himself said (quoted in Berry & Rofel, 9). Ordinary people untrained in filmmaking were now filming anything they pleased, which led to the proliferation of independent filmmaking. Without the oversight of studio censors, these filmmakers were able to hone their craft and discover the kinds of stories that resonated with them. Corresponding to the increase in independent filmmaking was the explosion of amateur documentaries shot on digital video. The accessibility and mobility of this new technology allowed new documentarians to immerse themselves in the stories they shared and contributed to the embrace of cinema vérité, or observational documentary. These low-budget forms of filmmaking influenced a significant component of the era’s visual culture with their realist aesthetic. By beginning his career in the thick of both of these trends, Jia shared the same sensitivity towards marginalized groups and harked on the realism that defined China’s age of independent filmmaking.

The World: How It’s Presented versus How It’s Experienced

Jia’s rise to prominence is credited to his international acclaim. He made his first film, Xiaoshan Going Home (1995), while a student at BFA. The film won the Grand Prix at the Hong Kong Independent Short Film and Video Awards, which introduced Jia to international filmmakers and funding and enabled him to make his “hometown trilogy:” Pickpocket (1997), Platform (2000), and Unknown Pleasures (2002) (Zhu). All three were embraced by international audiences, but by virtue of being independently produced, they couldn’t be formally shown to Chinese audiences. To Jia, this meant his films fell short in that they couldn’t “impact Chinese culture” (Jia). But in 2004, he “miraculously reconciled with the Chinese State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television” and earned the approval for his next film, The World, to be commercially released in China (Zhu). Initially, some questioned whether going mainstream would compromise “the valuable ability to think independently and the courage to be challenging” (Chen quoted in McGrath 107). However, his thematic consistency across his works has “largely exonerated the director of the charge of compromising his vision” (McGrath 107). The World is set in Beijing World Park, a theme park for tourists to see and take pictures with miniature replicas of famous landmarks. In the film, Jia’s emotional inquiry into the lives of migrant workers reveals a dismal reality overshadowed by the luxuries and conveniences of globalization, thereby questioning the desirability of a more globalized world.

Near the beginning of the film, an extreme long shot presents the skyline of Beijing with the World Park’s replica Eiffel Tower prominently in the center of the frame. Juxtaposing the French landmark with Chinese surroundings points directly to globalization, the force behind China’s era of transformation. After the long take gives the spectator a few moments to soak in this backdrop, a garbage collector, very likely a migrant worker, enters the frame and walks to the center before turning around to break the fourth wall of the camera (Figure 11). “A film by Jia Zhangke” gradually appears, suggesting Jia’s sensitivity to this demographic and living up to his reputation of being a “migrant worker director” (Zhen 16). This director credit moment introduces a tension between background and foreground, as the globalization that’s changing China’s skyline also produces a burden, symbolized by the trash, for China’s marginalized workers to shoulder.

The entire film revolves around this tension between background and foreground, and between global and local. The World Park setting serves as a microcosm of the globalized world, as visitors can see Manhattan, Egypt, and India in just 15 minutes according to the tour guide audio message. The layout enables them to take photos with the scaled-down replicas of famous landmarks like the Leaning Tower of Pisa as a substitute for transnational travel (Figure 12). “Give us a day and we’ll show you the world,” one sign reads, framing the park as a place of transnational mobility. Behind the scenes at the park, migrant workers like Tao (Zhao Tao) oscillate between different national cultures to deliver culturally specific performances for patrons. In a sense, the workers themselves are engaging in a minimized transnational travel and also immersing themselves in national cultures (albeit in very exoticized ways) (Figure 13). However, Jia’s inquiry into the migrant world peels back the veneer of interconnectedness and cultural celebration to reveal a dark side to the labor behind China’s globalization efforts.

Once a vibrant, celebratory performance concludes, we follow the workers backstage and see lives full of discontent. Relationships are consumed by distrust — Niu (Jiang Zhongwei) is possessive and paranoid every time he can’t reach Wei (Jing Jue) on her cellphone, and Taisheng (Chen Taisheng) is unfaithful to Tao; money is extremely tight as some workers resort to stealing from their peers; some workers endure physical abuse; construction accidents kill young workers trying to support their families back home; and Tao feels trapped at the park and in her life, ironically contrasting the transnational mobility that the park claims to offer. The film’s score, composed by Giong Lim, consists of electronic dance music that imbues the film with a looming sense of melancholy. In an interview, Jia describes the “luxurious, but sad, dance numbers” as signifying “the real emptiness of the lives of Tao and her friends,” adding that “life’s heaviness fades when confronted by the silky lightness of dance and music” (Danvers).

Jia’s hyperrealist aesthetic is integral to the film’s overarching dread. The long takes in particular illuminate the emotional weight that the characters carry, even if they’re unable to voice their discontent. On a night out when Tao and her friends “try to be happy,” it quickly becomes apparent that wealthy businessmen flock to venues like this karaoke bar to pick up migrant women who they know are short on cash. In a long take, one of these men tries to seduce Tao with jewelry and clothes. He starts touching her inappropriately and doesn’t seem keen on letting her walk away, making the spectator viscerally uncomfortable. Finally Tao’s able to leave, and the camera slowly pans to reveal that a bystander, who’s most likely a migrant worker herself, has been watching the whole time but refrains from intervening or even saying a word. The exchange she witnessed is probably a familiar one, and one she’s experienced firsthand, too, but all she can do is internalize her emotions, a coping method that adds to the heaviness of a marginalized experience.

In another long take, Taisheng confronts Tao after she’s discovered his infidelity. Taisheng repeatedly asks what’s wrong, but Tao never moves her blank stare and ignores him. The emotional charge of this moment does not lie in the words they say, but rather in the subtleties of the characters’ expressions and the dragged-out moments of uncomfortable silence. The light by Tao illuminates her cold expression and we can feel the burning rage inside of her that only intensifies the more Taisheng probes (Figure 14). The long take captures the moments of intentional silence that convey an unspoken hardship that is Tao’s life, and now her unfaithful boyfriend has added to life’s heaviness that she must shoulder.

Jia employs the long take to cast a light on the dread that resides in the characters’ lives, but this formal technique is also a crucial element to the film’s hyperrealist aesthetic. The prevalence of long takes and long shots creates a Bazinian-style of realism that preserves the continuity of real time and allows the spectator to choose the details of the frame to focus on. Consequently, The World feels less like a staged production and more like an observational inquiry into the real world. Additionally, the camera appears to have agency, frequently wandering its gaze unmotivated by the film’s characters, which suggests that the story we’re watching unfold is being experienced, more or less, all around by the city’s migrant workers. The hyperrealist aesthetic is also a significant element of the film because it creates a stark contrast with the animated moments that reflect the characters’ innermost thoughts and emotions. These moments always occur when a character gets a text that elicits an emotional response. In one instance, Tao, having stormed out after an argument with Taisheng, is on a bus that happens to be playing a commercial for the World Park: “Travel the world without leaving Beijing.” She gets a text and the scene switches to an animated depiction of the bus she’s on. “How far can you go?” reads the text from Taisheng. From her point of view, we look up at the street lights and the sky, as if yearning to go somewhere far, but she can’t because she’s stuck in her situation. Another animated moment occurs when Tao reads Taisheng’s text from Qun (Huang Yiqun) and discovers his infidelity. After switching to animation, the scene shows the phone as being underwater while she reads “I’ll never forget you” as if Tao feels like she’s drowning. These animated moments reflect the characters’ innermost emotions more forwardly than any other scene, but the animation just doesn’t fit with the rest of the film almost as if these emotions don’t fit into the minimal domain of the characters’ daily lives. The artifice of the animation portrays these emotions as fantastical, like they don’t exist within the bounds of reality, or they serve as a form of escapism from that very reality. Either way, the animated moments speak to the characters’ inability to express themselves and alleviate the heaviness of life; all they can do is endure what hardships they face.

Part of Jia’s signature is the intertextuality of his films, particularly a “hybrid form of textuality” that spans different mediums (Zhu). His films frequently “incorporate intertitles, pop songs, radio broadcasts, TV listings, and newspaper clippings” that carry cultural significance to varying degrees (Zhu). This is an interesting facet of his filmmaking style to think about in the context of different audiences, as domestic ones would surely recognize more cultural references than an international spectator at Rotterdam would. Does this mean that Chinese audiences understand his films better unless foreign audiences do their research and decode the references? I don’t think that’s the point. I think the point is that any audience doesn’t need to be clued-in to every cultural reference; as long as you’re able to recognize the heaviness of life for the characters and their emotional experiences, you understand what’s most important. This is encapsulated in an emotional exchange between Tao and her Russian friend, Anna (Alla Shcherbakova), where the two are conversing in Chinese and Russian respectively (Figure 15). They can’t understand the specifics of what the other is saying, such as Anna telling Tao she has to change jobs even though she hates to do it, but they are able to register the emotional pulse of the other and that is what enables them to connect as human beings. In this scene, Jia is calling on his audience to let go of trying to understand every piece of information and instead pay greater attention to the emotional experiences of the characters.

This emotional language exercised by Tao and Anna is a through line in the film and is a powerful tool that enables Jia to explore the hardship of globalization. China’s embrace of the global market economy and the dramatic transformations it took to get there may improve people’s lives on the surface, creating opportunities for rural residents to find higher paying jobs in the cities. While politicians and economists certainly leaned on the promise of higher income and personal gain in selling reform to the Chinese people, no quantitative model is able to capture the emotional weight of being stuck in your life, powerless to change it. It’s extremely appropriate that the film begins with Tao walking through the dressing rooms asking for a Band-Aid, which symbolizes a downstream solution to a problem as opposed to tackling the root of it. Tao is unhappy with her life, and frankly most of her friends are, too. She keeps trying to find happy activities to change her situation, like dancing on stage or going to karaoke bars, but these fleeting moments of happiness don’t solve the fact that a globalized China has exploited the labor of migrant workers like herself and trapped them in hopeless states of stasis. Her suicide that ends the film is heartbreaking but predictable. It’s the final exclamation of the emotional journey Jia takes us on, punctuating the dismal reality of many of China’s overlooked migrant workers.

Still Life: Local Sacrifices for a Greater Good?

Two years after the release of The World, Jia debuted Still Life at the Venice International Film Festival, this time returning home with the coveted Golden Lion prize for best picture. His domestic approval and international success cemented him as one of China’s most renowned filmmakers. Still Life harks on Jia’s emotional sensitivity towards those shouldering the burden of transformation, which confronts and questions the helpless reality of racing against a vanishing town in the name of economic progress.

The film opens with a blurry pan over passengers on a boat who gradually come into focus. While the background remains blurred, three long takes scan over dozens of people without having a clear main subject until it finally settles on Sanming (Han Sanming). After the director title appears, we see more typical establishing shots of the landscape of Fengjie alongside the Yangtze River. Jia presents shots of people before shots of place to signal that this film is first and foremost about people, about individuals. This opening sequence and its play on image sharpness also establishes a disconnect between figure and background, consistent with the impact that the Three Gorges Project has on the residents of Fengjie. The rural setting is uncharacteristic of Jia’s filmmaking, which typically takes place in China’s cities, but the scale of the project makes this a site of transformation and upheaval that is consistent with the stories he chooses to tell. The Three Gorges Project, the “largest artificial project in Chinese history,” sought to build the largest hydroelectric dam in the world on the Yangtze River (Interview with Jia Zhangke). The subsequent rise in water levels destroyed dozens of towns that were thousands of years old and relocated roughly one million people to the Liaoning and Shanghai areas (Interview with Jia Zhangke). Plans for the project were drawn up in the 1950s, making it part of Mao’s Old Planned Economy and not one of Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms. However, the project similarly harks on the theme of favoring the global at the expense of the local, a harsh reality that is the subject of Jia’s meditation in Still Life. A tourist ferry guide announces on a speaker that the famous Tang Dynasty poet, Li Bai, used to come to Fengjie to write poetry about its scenic beauty, and that now “the world’s eyes look toward this region again thanks to the Three Gorges Project.” As the voice begins speaking about the world’s eyes, the film cuts to a television set broadcasting old footage of Chairman Mao, Deng Xiaoping, and of workers breaking ground on the dam’s construction site. The ferry voice, filtered through the speaker to sound less personal and more digitized, continues to say that “the people of this region have made great sacrifices for” the dam, but doesn’t dwell on it (Figure 16). The footage on the set represents the rest of the world’s perspective on the project. To outsiders, it’s a massive initiative that’s years in the making to provide a sustainable source of energy, ultimately a significant benefit for the country as a whole. And there may be sacrifices, but that’s not the focus because the scale of the benefit is too great. Still Life refuses to look away from the local sacrifices behind this project and contemplates the absurdity of so much hardship being caused by human decisions.

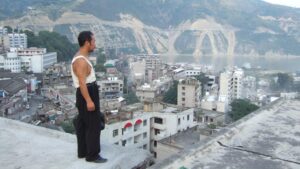

A moment of contemplative pause before a changing landscape in Still Life

Jia’s realist aesthetic places the audience in Fengjie as it’s being torn down so that we can partially experience the vanishing of the historic city as it happened in real life. Jia frequently uses documentary footage of actual demolition teams taking sledge hammers to buildings and had to speed up production so as to not miss the short window before the town was completely destroyed or submerged. Like in The World, Jia’s realist aesthetic lends itself to a slower, more contemplative pace in which plot is subordinate to the character’s and camera’s struggle to understand how this is reality. There are multiple instances in the film where long takes longer, even after characters have left the frame, as if to sit in sad moments of internalizing the hardship brought on by the construction of the dam. One of these moments occurs when Sanming visits his old home, only to find it’s already completely submerged by the rising water. In the long take, his driver tells him that his street used to be where the water now is and Sanming gets off the bike to look around and make sense of the situation. The camera tracks him as he looks out onto the water, like it’s right there with him as he realizes his old home is gone (Figure 17). He gets back on the bike but the camera doesn’t track him this time – it continues gazing out towards the water as if thinking about the many others who already lost their homes under this body of water or are going to in the near future. Another time, Tao (Zhao Tao) meets a 16-year-old girl, Chunyu, who’s trying to find a way to leave Fengjie and asks if she can be a maid wherever Tao’s from. Tao’s unable to help her and exits the frame, but the camera lingers on Chunyu watching, meditating on her dire need to leave and the struggle for her and so many others to do so (Figure 19). In a 1997 essay titled “My Focus,” Jia discusses his commitment to confront harsh truths: “I’m willing to face the real, although in the real there are flaws or even filth … I’m willing to gaze at it quietly … we do not raise our camera after the gaze to let the verdant hills and green waters dissipate the sorrow in our hearts. We have the strength to carry on, because I do not avert my gaze” (quoted in Zhu). These subtle moments of contemplation quietly give due time to the negative impacts on individuals caused by the project instead of glossing over them, like the ferry voice and television set, which ultimately question and therefore challenge the discourse that the benefits of the dam outweigh the local sacrifices behind it.

Jia doesn’t shy away from revealing the obstacles created by the vanishing of Fengjie on a very human level. Our two protagonists return to the area trying to find old family members before the town floods, and they lose touch completely. While they both locate their respective family, there is no reuniting, and they leave empty handed. Throughout the film, we also see the prevalence of work accidents, as some characters have lost a limb, or, in the case of Brother Mark (Zhou Lin), their lives. Workers are laid off and upset with their managers, and residents beg their local officials for help or guidance through this upheaval, to which those in power are simply unable to do anything for them; they’re left to fend for themselves. Moreover, the flooding of the town also means the vanishing of many cultural and historical relics with it. Tao meets an archaeologist, Dongming (Wang Hongwei), who’s racing to dig up a 2,200-year-old tomb from the Han dynasty. As he’s explaining this, the film abruptly cuts to a close-up of a hammer smashing a brick wall, eliciting the feeling that these ancient artifacts are being destroyed as they’re lost to the water.

The rapid transformations China’s experienced are so dramatic that they border on unbelievable, which is the reason behind the film’s’ surreal atmosphere and moments. As one of the characters says, “A city that took 2,000 years to build was demolished in two days.” In an interview about the film, Jia talks about the “contrast between the numbers 2,000 and two,” which he thinks is “very surreal …. Surrealism is part of China’s reality, such as the speedy changes. It’s beyond human logic” (Interview with Jia Zhangke). To Jia, it’s hard to imagine how the reality of a vanishing Fenjie and all the people it displaced could be caused by the construction of a dam. Instead it feels more like “after a nuclear war or alien attack” (Interview with Jia Zhangke). Consequently, the film’s electronic score contributes a mystical, sometimes extraterrestrial mood to scenes. Of course, there are also the moments in the film that stand out where it seems aliens are involved in some way, such as when the pagoda blasts off into the sky like a rocket, pointing to the extraordinary speed with which buildings in the area are being demolished and disappearing (Figure 20). In another surreal moment, Sanming looks out onto the water, similar to when he realizes his old home is submerged, and sees a UFO fly through the sky. The scene cuts to a reaction shot of Tao watching the same alien aircraft, which binds the two storylines with the shared experience of not being able to believe what’s happening to Fengjie.

Still Life tackles the tension between global and local by being set at the site of a project whose impact is far reaching, boasting the world’s largest power station, but also at the expense of many people’s homes and livelihoods. Jia doesn’t explicitly critique the Three Gorges Project, though, but rather employs a voiceless emotional charge that affects a somber coming to terms with the cruel realities that the people of Fengjie face. This charge courses through the film, contemplating the absurdity of a rapidly vanishing town that’s so calamitous it’s almost beyond imagination. It’s fitting that he titled his film after a style of art that depicts inanimate objects because the animism of his cinema injects life and a soul into Fengjie through the emotional contemplation of his characters and his camera, making the loss of the town all the more painful.

Conclusion

Jia Zhangke began his career outside of the studio system, which gave him the freedom to make films untouched by censors but also prevented him from reaching his compatriots, essentially making his earliest films a window into Chinese society but not something in conversation with Chinese culture. The emotional sensitivity he brings to his filmmaking refrains from making overt criticisms about Chinese society, but it does imbue these films with a sad questioning of reality, as if to propose that the status quo is falling short for some populations, namely marginalized groups like the migrant workers who make up much of the urban population.

The West’s obsession with capitalism has long painted China’s rocky 20th century as repeated flukes of communism. While the CCP certainty isn’t exempt from political mishaps, the country’s embrace of capitalism, a subtle form of westernization, warrants the same critical lens as the many other political movements that went awry in the 20th century. Additionally, Jia Zhangke’s documentary aesthetic is an ideal window into the lives of some of China’s marginalized groups, as it allows him to reveal the hardships they endure, critically commenting on Chinese society while bypassing the notoriously strict state censors.

Works Cited

Berry, Chris, and Lisa Rofel. “Introduction.” New Chinese Documentary Film Movement : For the Public Record, pp. 3–14.

Danvers, Louis, and Jia Zhangke. “Shije (The World).” Kfda.be, KunstenFESTIVALdesArts, 16 November 2005, www.kfda.be/en/program/shije-the-world.

“Interview with Jia Zhangke.” Still Life, produced by Xu Pengle, ang Tianyun, and Zhu Jiong, Xstream Pictures, 2006. DVD.

Jia, Zhangke. “Filmmaker Jia Zhangke on the Realist Imperative (at Asia Society).” Youtube, Asia Society, 10 May 2010, www.youtube.com/watch?v=EX7fAsYMbx0.

Li, Shi. “The Economic Situation of Rural Migrant Workers in China.” China Perspectives, no. 4, 2010, pp. 4-15,149. ProQuest,

http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/scholarly-journals/economic-situation-rural-migrant-workers-china/docview/1496660897/se-2?accountid=14244.

McGrath, Jason. “The Independent Cinema of Jia Zhangke.” The Urban Generation, 2007, pp. 81–114.

Opening the Door: How Deng Xiaoping Transformed China’s Economy. Films On Demand. 2008. Accessed 18 February 2021. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=102632&xtid=40670.

Zhen, Zhang. “Introduction: Bearing Witness: Chinese Urban Cinema in the Era of ‘Transformation.’” (Zhuanxing)” The Urban Generation, 2007, pp. 1–48.