Cure (1997) Review: Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Nightmarish Descent into Nothingness

Campbell Mah

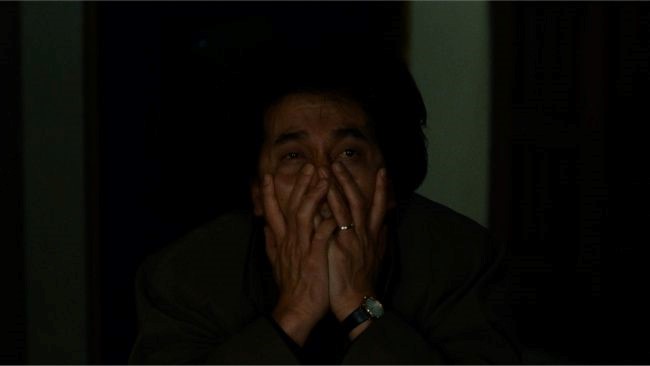

Kōji Yakusho in Cure – Daiei Film

Japanese filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 1997 film Cure refuses to be bound to a single genre. It’s equal parts a police procedural/crime thriller in the same vein as The Silence of the Lambs (1991) or Se7en (1995) and a work of pure psychological horror. The film is often considered a progenitor of the Japanese horror (or J-Horror) phenomenon that gained immense popularity throughout the nation’s media in the late 1990s, characterized by themes of the supernatural and including such films as Ring (1998) and Ju-On: The Grudge (2002). If anything is definite, it’s that Cure is a film that revels in the ambiguous; leads trace into obscurity, questions are met only with more questions, and the bloody Xs slashed on the throats of a string of murder victims do not mark the spot. Rather than descending further into the revelatory details of the film’s central mystery, we instead spiral down the cavernous depths of the human mind. In doing so, Cure subjects us to the hidden terrors of the psyche—those violent impulses that remain unforeseen and unknowable to even ourselves until we hold up a light and approach them in the darkness.

The plot of Cure is a labyrinthine one; Detective Takabe (Kōji Yakusho) is strewn about Tokyo as a wave of unexplained murders plagues the city. Adding to his worries is his mentally unstable wife (Anna Nakagawa), who, while good-natured, proves to be a source of significant frustration for an already weary Takabe. As Takabe scours the streets for clues with the aid of his psychiatrist colleague (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), it becomes apparent early on that a sinister force is at work. A former psychology student—or perhaps the literal personification of evil—known only as Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) appears like a ghost, drifting in and out of the frame, often shrouded in darkness. While his ability to kindle acts of depraved violence poses a real threat to Takabe, Mamiya’s existence as depicted on-screen is anything but definite, making his hallucinatory mind games all the more terrifying. Kurosawa’s story is devilishly calculated and hauntingly reticent; scenes often reveal just enough information to propel the plot forward but hold back fully satisfactory explanations, generating additional layers of confusion that place us in Takabe’s increasingly fractured headspace.

Reality is rendered ambiguous in Cure, primarily due to the film’s rich atmosphere that imbues it with a thick haze and lends itself to a certain dream-like quality. Our first introduction to Mamiya takes the form of a mirage; Kurosawa cuts from a shot of an empty beach to that of an unwitting victim curiously staring at something off in the distance—something of a reverse eye-line match. Like an apparition, Mamiya appears ashore, suddenly present in the initial shot. As the ghostly figure approaches his victim (and the camera), the sound of waves crashing reverberates in the background, lulling us into a trance-like state. Throughout the scene, Kurosawa frames both characters in an enigmatic extreme long shot, keeping Mamiya at a deliberate distance to obscure his face and thus his intentions from us—painting him as a hallucination. Tiny white specks that bizarrely twinkle above Takabe’s head during a shadowy interrogation scene feel more like a natural outgrowth of the film’s hazy aura rather than an aberration, compelling us to question the validity of both the scene as a whole and our perception of it. Takabe’s final confrontation with Mamiya likewise feels separated from reality, both by virtue of the eerily desolate soundscape of the scene—save for the hollow gusts of wind that blow continuously in the background—and the literal haze that envelops Takabe as he makes his way toward a twisted kind of Purgatory.

Masato Hagiwara in Cure – Daiei Film

No discussion of Cure is complete without mention of its masterful attention to sound. Mamiya’s acts of hypnotic suggestion are not only visually but sonically mesmerizing. The rhythmic pattering of water or the flicking of a lighter overpower and emerge at the forefront of our senses, lulling us into their gentle susurrations and rendering Mamiya’s control over his victims eerily palpable. About midway through the film, Mamiya uses a pool of spilled water to hypnotize a doctor before waking her by splashing water on her face. Just as the doctor is brought back to her senses by the abrupt sound, we are too forced to recollect ourselves from Mamiya’s mind games, only to be drawn further down the rabbit hole. A slew of ambient noises also permeates the film’s sonic landscape; however, their placement infuses these ostensibly innocuous sounds with an acutely sinister edge. The idyllic chirping of birds plays over the senseless killing of a policeman. A blaring railway signal becomes an even more dire warning. Evil surges through the city like the sound of water rushing through pipelines and pulses to the buzzing of fluorescent lights. Not even Takabe’s own home is spared from the incessant low humming of an empty washing machine—a noise that we observe is equally capable of conjuring up murderous intent as the flick of Mamiya’s lighter.

In addition to its striking sound design, Cure is bolstered by two equally hypnotic performances, each playing off the other to generate a constant push-pull dynamic of power and mind control. Detective Takabe, played by Kōji Yakusho in his inaugural collaboration with director Kiyoshi Kurosawa, swings from coolly aloof to shockingly violent in a matter of seconds, becoming more volatile and unhinged as the film progresses. Yakusho’s performance is grounded with just enough humanism to allow us to sympathize with his plight but enough restraint that leaves his motivations ambiguous. Then we have Mamiya, a walking enigma chillingly portrayed by Masato Hagiwara with a menacing allure that’s simultaneously captivating and terrifying. Unlike Yakusho’s detective, who sporadically bursts into fits of hysteria, Hagiwara’s performance embodies a perpetual state of emptiness—an impression of nothingness so palpable that it feels dangerously contagious. The interplay between these two actors (especially during interrogation scenes) is nothing short of riveting, making for one of the most memorable aspects of the film.

Kōji Yakusho and Masato Hagiwara in Cure – Daiei Film

The pervasive feeling of dread that Cure induces isn’t necessarily derived from its grisly images or even the creepiness of its killer. It’s from the primal fear of being overtaken by nothingness—our sense of self erased, our souls hollowed out and replaced entirely by some foreign entity, our bodies becoming empty vessels for destruction. As wisps of smoke from Takabe’s cigarette dissipate into thin air in the film’s final scene, one can only feel an impending apocalypse awaiting the city and its unknowing inhabitants. In presenting us with a question (what is the reason for these gruesome killings?), Cure leaves us without an answer, only traces that bear the mere semblance of one. Is it due to the cursed phonograph that Takabe listens to at the end of the film? Maybe it’s hypnosis and the power of suggestion. Or perhaps it’s something even more primitive, hidden deep within ourselves—a virus inextricably infused within our lifeblood—but ultimately obscured from our conscience in a veil of darkness. Whatever the case may be, Kurosawa’s work of cinematic hypnotism makes it hauntingly clear: our predicament is anything but curable.