Cosmic Rays Film Festival 2022

Introduction by Campbell Mah

After being canceled in 2021 due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Cosmic Rays Film Festival made its fourth annual return to Chapel Hill, NC on March 31st and April 1st, 2022, celebrating the works of experimental filmmakers that expand our idea of what film is and explore the possibilities of what the cinematic medium can accomplish. The editors of Aspect: Journal of Film and Screen Media were fortunate enough to attend all four programs of this year’s edition of the festival, which took place at both the Varsity Theatre and the Forest Theatre in Chapel Hill. The following reviews highlight some of the Aspect team’s favorite short films showcased at the two-night event—those whose formal inventiveness and creativity not only emphasize the exciting nature of experimental cinema but also lend us a surreal sense of insight during an equally unconventional era. In addition, we were lucky to be able to speak with some of the filmmakers whose work was shown at the festival and gain a deeper insight into their creative processes.

Wear and Tear

By Campbell Mah

Photo Credit: Jason Robinson

Jason Robinson’s Wear and Tear weaves together Super 8 footage, voice recordings, email fragments, and other digital extracts to create a free-form narrative that reflects the general state of anxiety and malaise that many of us have found ourselves feeling amidst these particularly uncertain times. Set to the backdrop of a sunny afternoon at the beach—a place of supposed escape and refuge from the harsh realities of life—the short’s juxtaposition between nostalgic imagery and excerpts from our pandemic reality make for a final product that is both wholly relatable and deeply uncomfortable. Director Jason Robinson, a collector of Super 8 cameras, shot the entirety of the short’s footage over the course of a few days at the beach with a couple of rolls of film that were nearing their expiration date. It was months later, in the dead of winter—one of the darkest times during the pandemic for Robinson personally, that the construction of the short film began. “I already felt so disconnected from the previous summer when I filmed it that I approached the images like found footage, which a lot of people have assumed it is,” says Robinson, a statement that explains the disquieting sense of unease that the film evokes.

The initial idea for Wear and Tear was sparked by Robinson’s research into allostatic load: the long-term effects of continued exposure to chronic stress on the body often referred to colloquially as wear and tear. The short is divided into four sections, with each segment’s title corresponding to a variable used by scientists to study the human stress response at its peak. According to Robinson, every single second of the film is autobiographical, with elements taken directly from random thoughts written in the notes app of his phone, voicemails from friends, and phrases he found himself constantly repeating in emails. “My goal was to use this deeply personal and specific oversharing to capture feelings that were universal with the hope that I wasn’t the only one feeling that way,” says Robinson, which—for me—he absolutely did.

The following is from a brief Q&A that I conducted with Robinson over email.

What would you say is your biggest influence as an artist?

So many things! I felt very fortunate to be able to attend Cosmic Rays in person this year and screen alongside so many artists that I find inspiring like Charlotte Taylor, Lydia Moyer, Lori Felker, John Muse, and Brendamaris Rodriguez. Also I just saw the Laurie Anderson exhibit at the Hirshorn in DC and it’s all I’ve been able to think about, just heartbreakingly beautiful and perfect.

What advice do you have for aspiring student filmmakers, particularly those interested in creating experimental film?

Pay attention and remain open to aspects of wonder. We train ourselves to tune the world out and get to our destination as fast as possible. Listen carefully, look around and document the things that interest you, with a camera, sound recorder or a notebook. Once you do this for a while, ideas and images for films will start to become apparent.

giroscopio

By Ana Hoppert Flores

Photo Credit: Brendamaris Rodriguez and John Muse

giroscopio (dir. Brendamaris Rodriguez and John Muse), like many of the films showcased at the Cosmic Rays Film Festival, is a pandemic film—not necessarily because of its content, but rather because of its timing. For Rodriguez, giroscopio stemmed from boredom. When asked at Cosmic Rays about how she came to collaborate with Muse on this project, Rodriguez responded that it “began from the isolation … I [was] bored.” Rodriguez, an artist, filmmaker, and performer based in Puerto Rico, met John Muse, artist, filmmaker, and professor based in Pennsylvania, in 2019. The two artists reunited during the pandemic over their need to create something, using “Zoom meetings, emails, [and] WhatsApp” to bridge the creative, and geographical, divide between their homes.

giroscopio is a film that melds cultures and languages together through, as Aspect editor Campbell Mah noted to me, its “unifying sense of motion [and] visuals.” Its distinct feeling of whiplash is one that reminds me of the uncertainty distinctive of the time when its proposal was first conceived. For instance, the most striking scene showed a sequence of pictures flashing in succession as if they were individual slides on a projector. A voice naming objects and nouns would speak, and another voice would respond, saying the word’s Spanish equivalent but not always corresponding with the image being shown. The series of pictures flashed across the screen, each one appearing a second earlier than the one shown before it, until all of the pictures melded into a blur.

The scene’s effect was disorienting, but tangible—likening itself to the feeling you get once you’ve fallen after spinning around in circles, or when you’re on a spinning ride at a park, or the feeling of when you’re on a spinning ride at a park that makes you shut your eyes tight and hope that it’ll stop. For a film named after a gyroscope, it seemed only natural that I felt a sense of dizziness and stimulation overload while watching that scene. It made me feel viscerally alive.

Rodriguez describes the making of giroscopio as being “really challenging, but very fun.” Her and Muse’s use of pre-existing multimedia to create a new piece of art might not reference the pandemic outright, but the feelings that their film invokes might instead point to its existence as a piece of anthropology, or a work of art that can’t help but be impacted by the worlds of the artists who create it.

The overstimulation caused by giroscopio’s purposeful mispairing of objects and words is reminiscent of an unsuccessful attempt at giving the abstract meaning, or trying to name a feeling that can’t be described with words. Instead of trying to find the perfect word to encompass a feeling that can’t be expressed, giroscopio allows its audience to revel in this feeling of the chaos and its proceeding numbness—a feeling so able to be felt that, in times of boredom, isolation, and nothingness, it can remind us of what it can mean to feel in the first place.

Harvester

By Campbell Mah

Photo Credit: George Jenne

Harvester presents us with another glimpse into the chaos of the current day, except this time, it’s through the crimson-tinted sunglasses and plastic fangs of George Jenne as a bloodthirsty, world-weary vampire. Jenne’s vampire spouts a long-winded monologue about living in these contemporary times of “unadulterated stupidity,” lamenting the eternal terrors of rampant consumerism, fast food, and modern-day ennui. While much more minimalist than many of the other festival entries, the short elicited a heavy amount of laughter from the audience, and Jenne’s comedic performance was one of the highlights of the evening. Harvester lovingly pulls from its horror genre influences and gives us a refreshingly fun take on the monstrous absurdities of our new pandemic reality.

Glazing

By Liam Bradford

Photo Credit: Lilli Carré

Lilli Carré’s Glazing is a charming and remarkably elegant expression of reflexivity and the female form. The short animation features a beautifully spare watercolor style of animation, featuring just one woman, naked and pink, set against a completely white background filled with the sound of a crowd having lively, but polite conversation (the kind you might find at a well-attended gallery showing). The woman moves dynamically around this strange space, sometimes in realistic mannerisms and other times through cartoonish, elastic morphings into different shapes and positions that play with the viewer’s perspective through clever bendings of shape. These shapes imply elements of the space through her interactions with it. As she moves around this implied space she assumes poses that emulate iconic images of the feminine form, yet she can never seem to settle on one that she likes. Our involvement in this cycle grows as the viewer enters, begun by the sound of the diegetic audience but further developed through the body language of the woman as she assumes and rejects forms. The film ends when the woman finally stops assuming forms and beings to investigate the audience. She stands back, trying to get a better look. She weighs our character and form by looking, just as we have done to her. Then, she exits stage left and we are left with the white background, invited to consider what has happened to us.

Pretty is as Pretty Does

By Ben van Welzen

Photo Credit: Jenny Stark

Jenny Stark has a lot to say about the South. Her film Pretty is as Pretty Does manages to communicate her nostalgia and criticism for the Southern landscape and culture in a disorienting black and white kaleidoscope of the sights, sounds, and memories of the region. It all starts with the distorted and slowed down voice of Reese Witherspoon listing what Stark called in a Q&A “polite to white people” films about the South like Forrest Gump, The Help, and Terms of Endearment overtop flickers of a Southern villa. Immediately, Stark has taken a mythologized and romanticized South and turned it on its head, imbuing a spirit of anxiety and unease into what have become symbols of comfort. For the next seven minutes, the film presents an impressionistic onslaught of Southern images from pecan pie to confederate flags while a whispered voice narrates classic Southern phrases and manners. The sounds of cicadas, the woods, and open fields begin to morph into a cacophony of a growing storm and eventually the film breaks into a swirling hurricane of rain-covered fury pierced by thunder and lightning. The film becomes an object of the storm as images only appear with the crack of lightning and the lens gets soaked in a wash of rainwater. However, for all of the uneasiness Stark manages to conjure up, there is still a pervading feeling of warmth and nostalgia. Though the cicadas are overbearing and the storms are destructive, Stark’s meticulous filmmaking finds comfort in these images and sounds as a reminder of home. Nevertheless, none of the images of the film last long enough for the viewer to latch onto and take in; we’re left to longingly look through the window to an ever-fading and ever-furthering time and place of chaos, anxiety, and beauty.

The following is a virtual interview I conducted with Stark about her film, her experience as an artist during the pandemic, and art about the South more generally. The transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Going back to the very beginning, where did the idea for this film begin? You spoke briefly at the Q&A but we didn’t have time to touch on your relationship with the South if you’d like to discuss that as well.

Yeah, so I’m from Houston, so that was one of the things that I was worried about, like do I seem like some California interloper making something from the South that I don’t know about? But I live in Davis, California so I’m not near L.A. or anything like that but I do remember seeing a movie that was based in the South when I first moved here. I can’t remember what it was but it was a really sad movie — it was based in Texas actually — and people were laughing just at the accents and they thought that everything was funny because of the accents while I was thinking that these were real people experiencing real pain. Then five years later people all over seemed to get obsessed with South in kind of a more bougie way, like fancy comfort food — all of the sudden you’re making shrimp and grits for somebody and they think you’re a genius. So that was really interesting but also just coming from the South and my mom passed away fifteen years ago so then it becomes this project to try to remember the goofy sayings she said. I used to actually look up lists of Southern sayings and that’s probably what brought me to Reese Witherspoon and all of that. I should also say that I like the Bitter Southerner too, so I don’t just partake in super mainstream stuff, I do try to keep that alive in myself as I’ve been gone from there for a long time.

Going off of that, your film feels like a balance of real Southern experience along with some sort of memory and feeling of the South, which comes across very strongly in the film’s impressionistic style. Could you speak more about what drew you to make this film the way you did as opposed to something more narrative-focused?

I have made narrative films before but I do feel like my experimental films reach more people. There’s such great narrative work out there, and I haven’t given up participating in that — I love documentary and narrative that has very real dialogue to see these people and their story — but I honestly feel like I have a knack for experimental films. I almost feel like my narrative stuff is more experimental than my “experimental stuff” and I just enjoy seeing narratives more than I enjoy making them. It requires massive amounts of people and crews and performers who aren’t so easy to come by in this part of California. Then I also had a sudden life-change and I just thought “y’know I used to make these experimental films, there’s this history of experimental film that I love, and within my world the way it is right now, I can sit by myself and make these things.” So it’s been an easier way to work when I have other constant responsibilities.

To that point of making these more personal films on your own time, I feel like we have to talk about the last two years of COVID and how that affected your process or your timeline. So with such a personal and reflective film, how was it different in these circumstances?

So I actually created a proposal for this piece that was for a performance-type piece. I had this elaborate thing that I proposed to the San Diego Underground Film Festival where the list would have been performed in person, so I would have been there performing the whispering, and then my nephews are the musicians and they would’ve performed live. Then San Diego Underground said they wouldn’t do the in person performances but then one thing that happened that was actually really good is Bill and Sabine [the organizers of Cosmic Rays] made their deadline the first of January. So I could work on it until then and then I can have my Christmas break time to just completely finish it, record the audio, and really just work frame by frame to get it done. Earlier on I had put it away, it was pretty close to being done and planned out, and then I brought in a lot more textures and footage and figured out what I wanted the structure to be. Then I just went back and worked on it frame by frame.

So since you mention that, was this something you saw from the beginning? I couldn’t tell if this was all found footage that you edited together or if you went out and did some filming yourself or maybe something else, but did the image you started out with change at all over the course of making the film?

A lot of it is shot by me, like I even shot the forest that was behind the [Forest] Theater when I was there for Cosmic Rays before the pandemic. I also shot some stuff with my dad driving me around on a dune buggy in Texas because he had a little cabin between Houston and Austin. But there’s also a whole lot of appropriated material, especially of the storms. There’s also a combination of Southern storms and horses being saved from water but then I also have horses being saved from fire in California, so there’s kind of a combination of those and I’m thinking about how much of the South is actually shot in California and then also how I grew up in storms and how fires have replaced the storms. But since I started I had planned for there to be a build up of storms and I definitely had the slowed down Reese Witherspoon. Then over the last year I was collecting quilt imagery from all over the place, mainly stuff that’s for sale and not anything that’s famous, just stuff that people post on their own sites. So that’s what I was mostly collecting recently and I felt like making it was a little bit like quilting because there was a pattern to all of the visuals, that pattern being a loop of lightning in the sky. So I took flashes of lightning and looped them to make the images just show up when the lightning comes up, then as it gets more intense the images show up faster and faster.

In the description of the film you had mentioned a reappropriation of the South through Pinterest and new social media, so I’m interested to hear your thoughts on how all of these new media are reshaping a perception of the South.

One of the things I thought of when I heard Reese Witherspoon chirpily listing off Southern movies like Gone With the Wind was those conversations where a family member will say “well I really like The Help and I feel like back in the day our family would have been like the good family in The Help” and then I’ll say “well that’s what that movie is made to make you feel.” So you don’t get a lot of people talking about movies like 12 Years a Slave, which is still a movie about the South. It’s interesting what people think of when they think of “Southern comfort movies,” movies that make us feel good about being from the South. So that’s interesting but there’s also depictions that are so obviously California versions of what the South is. Like in Sweet Home Alabama her parents have Confederate flag pillows and I wonder if they are really depicting what is really happening in Alabama or is that what some California producer/writer/director thinks is happening in the South. There are two different things: there are the films that make our family members and people older than us feel really good about being Southerners and then there’s this outsider view about what the South is really like, but neither one is really accurate and based on personal experience.

So to finish off, do you have any advice or any words you’d like to share with aspiring filmmakers?

I think you need to deal with a subject and a way of working that you’re passionate about. I really enjoy the technique I used in this film, it’s incredibly meditative for me to go back frame by frame and overlay a bunch of textures, it’s overly fascinating and I could’ve worked on it for ten more years. So find the technique that you really like to work with and also a subject or a script or anything that can sustain you for a long period of time. You will get tired of it because you have to watch it a billion times, but for me I wasn’t ready to let go of this film. So that’s the goal, is to find something you find that way about.

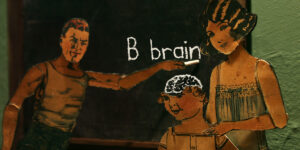

The Ephemeral Orphanage

By Ben van Welzen

Photo Credit: Lisa Barcy

Lisa Barcy’s The Ephemeral Orphanage opens with an enigmatic image that immediately outlines the rest of the film: a meteor made out of a crumpled piece of paper flies through the stars in the vastness of space, leaving a wispy trail on its tail as a chaotic assortment of strings and woodwinds accompanies its motion. In the space of twenty seconds, Barcy has established the film’s stop-motion animation, central idea of space, and consistent air of joyous mystery. What follows from this prelude is a playful story of a group of children trying to experience the wonders of the galaxy within the confines of a tyrannical orphanage. With her charming animation style and evocative score, Barcy manages to deliver this story with the youthful spirit of the orphans; the use of newspaper clippings, chalk, and crayons makes the film feel like the product of the childrens’ imagination, as if they themselves found scraps of paper lying around and decided to make their own fantastic story. Heads fall off and turn into kickballs, galaxies become brains which then become clouds through which the children fly, and men turn into bubbles which will then become seeds that grow into lunar plants that sprout limbs. Like many films in the festival, The Ephemeral Orphanage comes across as the passion project of an artist trapped inside by global circumstance. However, Barcy has taken our collective isolation and looked out the window to the skies and beyond to find the boundless fun and heart that will always be found in the minds of children.

SON CHANT

By Ben van Welzen

Photo Credit: Vivian Ostrovsky

Vivian Ostrovsky’s SON CHANT is a celebration of the prolific filmmaker Chantal Akerman and her close friend and collaborator, the cellist Sonia Wieder-Atherton. Ostrovsky was a friend of the two artists and came across old footage of the three of them, inspiring her to make a film about the pair. The film is a series of her own footage spliced together with clips from Akerman’s films and of Wieder-Atherton’s music but as the film progresses, Ostrovsky blurs the line between the sound and image of the film. In one striking moment, the film image is replaced with the sound wave from the audio we are hearing, forcing the sound to dominate the image. However, Ostrovsky’s film is one of harmony, whether that be between director and musician, across sound and image, or among all female artists. The film makes notable use of split screen, having Akerman and Wieder-Atherton share the screen while being in their own separate frames. Similarly, Ostrovsky shows the whole film strip, which includes the images as well as the optical sound frequencies that run alongside it. By the end of the film, the sound and the image become one, each coalescing into a singular voice, just as Akerman’s camera harmonized with the voice of Wieder-Atherton’s cello. Ostrovsky then generalizes this experience and broadens it to the city life that she, Akerman, Wieder-Atherton, and so many artists inhabit. In a way, the film demystifies the complicated work of Akerman and inspires new artists to find a passion like the three women of the film. SON CHANT is not just a documentary giving a closer look into the lives of a filmmaker and a musician, it expands the canon of their work to welcome voices old and new into the boundless realm of art.

The following is a virtual interview I conducted with Ostrovsky about her film, her use of sound, and her relationship with Chantal Akerman and Sonia Wieder-Atherton. The transcript has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Starting off, what inspired you to make this film?

I met Chantal in the 1970s and we remained friends ever since, meeting in Paris, New York, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and our paths crossed various times. I loved her work and I very much appreciated her as a filmmaker, as a friend, and I appreciated her sense of humor. We had common things in our background also, our culture, this middle European background, the stories that we had heard of during our childhood, World War II, our parents generation. After she died, there was a memorial service for her in Lincoln Center and they asked if I wanted to speak and I said no but I wouldn’t mind contributing some short filmic material. So I made a first film about her and that was right after her death. For two years I had shot on mini DVs, and instead of Super 8 material where you have to keep close records, you can see the result of DVs immediately so I kept the cassettes and put the date on it and wouldn’t pay much attention to it. Years later I took my boxes of mini DVs, and I had about 200 of them, and I decided to really go through all of them. I thought most of it was flat and boring until I got to the end and I found this snippet of film we had had with Sonia, Chantal, and myself, and I really liked that little bit of film. I knew a lot about Chantal and I knew that she had lived with Sonia for a long time and even after they split up, Chantal would immediately call Sonia when anything serious happened so I knew that their collaboration meant a lot to both of them. I knew for Chantal that Sonia was like a pillar in her life and I had gone through a lot of the interviews and articles that were written about Chantal after her death and I noticed that one of the things that the articles did not mention that much — they mentioned the Holocaust, the rhythm of her films, the takes and the camera — was her use of sound, which I thought was one of her fortes. So I thought I’d make a film about their collaboration which was so important to her films and so important to both of them.

Something else I wanted to talk about was exactly that use of sound, which I agree isn’t talked about enough. In your previous work, how have you worked with sound?

Well I forgot another detail about where this film comes in in the scope of my own work. There’s a movie house here in New York called Film Forum that acts kind of as a cinematheque for me. I was commissioned by Film Forum to make a short film between two and four minutes of whatever I wanted but with no sound. For me sound is always a really important element, and it has the same importance that the images have. So after toying around with ideas I came up with a work called Unsound which is a film without sound but it’s about sound. Chantal’s film came after that so I really went back to using the sounds in her film.

So after you had met Chantal, what was your relationship with Sonia?

Well first I met Chantal and then afterwards when we got closer she introduced me to Sonia. They were still living together at that point but actually Sonia was really important to Chantal because she introduced Chantal to music. When they met Chantal was kind of depressed and she was sleeping a lot; she had nowhere to stay and somehow she ended up staying in an apartment where both she and Sonia were staying. Sonia rehearsed like eight hours a day and Chantal slept many hours a day but when she’d wake up, there was Sonia. So Chantal, being a very good observer, started focusing on Sonia and her cello, and then she really got into using music a lot. Chantal filmed Sonia a lot also, there’s a series of films called Around Sonia Wieder-Atherton.

In your work how do you manage to maintain that importance of sound relative to image? Does the sound ever come before the image?

I started out as a Super 8 filmmaker and I shot silent material because the sound track was very thin and very poor, so I never used direct sound. So I come from that place, I would very often start editing and edit about three quarters of the film and sound would come in later. Obviously there were some moments when I thought of putting this or that sound in, but usually it was after having around three quarters of a rough cut that I would start coming in with sound. Even now when I shoot on video I very often add or subtract sound from those and use other sounds.

What was your experience making a found footage film? What new mindset do you have to take?

Well today it’s tricky because you’re sort of embedded in images, everywhere you go, you take the ride on the elevator here and you have images, it’s almost too much. So when I started using found footage it was one thing, today when I use found footage I usually try to do something to it so it’s not just face-to-face found footage. I try to process it in some way to make it my own, otherwise it loses its interest. But I love filmmakers like Bill Morrison whose work is purely found footage and Gianikian and Ricci Lucchi who worked on beautiful archival footage together that they processed and changed the look of. So that’s a different take on it but I love researching and working with found footage but I really find that I have to do something to it to make it my own.

History of Noise

By Liam Bradford

Photo Credit: Stella Rosen

Stella Rosen’s History of Noise is a beautifully animated meditation on noise pollution and how it exploits the inner mechanisms of our brain that we have inherited from millenia of evolution. The film traces us through a concise progression of evolution, first showing us the process of our common ancestors learning to use sound as an alert to identify danger, represented as a bell in the brain of these animals, and then showing us the same bell in one of our brains as it is bombarded with the sounds of lawn mowing, cars, and chainsaws. The film ends with the human tearing out the bell from their ear, frustrated with its incompatibility with our modern world. The animation in this film features earthy, dusky tones and paper-grained textures that render the slick transitions and colorful imagery of this film in a beautifully approachable aesthetic that feels grounded and real. The soundscape is equally impressive, as the initially sparse sounds, which are imbued with an impressively tactile ambience, build into a cacophonous roar.

The following is from a virtual interview I conducted with Stella Rosen, minor edits for clarity have been made.

I noticed you studied biology for your undergrad, and your films all deal heavily with the natural world. Talk about your connection with nature and how it has affected your life and filmmaking.

Yeah, well, I mean, I studied bio in undergrad because I’m fascinated by the natural world. And I think a lot of my work revolves around the natural world, and our relationship to it. And a lot of what our relationship with nature is now is dealing with this kind of destruction, and this kind of bleak future we’re inheriting. So that’s, that’s been kind of a through line with my work is like, connection to nature. And I mean, I’m still totally interested in biology. And a lot of my inspiration for my work comes from like, walking in the woods and right.

So when did you start working on History of Noise? What was going on in your life at the time?

I started pre-production for that film in late 2020. Or, yeah, late 2019. I’m really bad with dates. I think it was finished in 2020. Okay, so yeah, it was late 2019. I was having kind of a sound sensitivity moment. It seemed like somebody was always mowing the lawn or somebody was always driving down the street and bumping their subwoofers and it was really, I was also living in this weird suburban subdivision in Southern California at the time. So just like, sprinklers were always on even though you know, there was a drought happening in California for the last I don’t know, so many years. I was just feeling very sensitive to my surroundings. And so I decided to make that film about noise pollution and how noises were originally meant to be construed by our bodies as signals of danger, or safety. And kind of show how that affects human ears and brains. Now, when we have this constant audio input, this constant like noise level, that is, it has serious psychological and health implications. I had some of my friends, they’re in public health right now. And they were like, we would love to see a film about noise pollution and the negative impacts. So that’s kind of why I made this piece. That’s where I was.

You mentioned walking in the woods is important to your creative process. Did you still have access to spaces like that in the neighborhood of Southern California you were in at the time? Were those spaces something that you sort of had to imagine? Or were you able to go somewhere and really think about it?

I was in this really Canyon-y area where there’s no rivers or anything like that. It’s like dry, right? A very mountainous area. I was able to get away on some weekends and go, like, drive an hour away and whatever. But yeah, a lot of it is just my imagination, and what I can remember. What I think, you know, the woods should sound like, and then I create it using what I have on hand audio wise.

Okay, so what about let’s talk about the sound design. What was your process? So for that, did you have collaborators or were you on your own?

Well, first, I always do a soundscape. For my pieces, I’ll lay background tracks according to what I want to like, come through at the very lowest level for viewers, and then I will design, heart effects and music. And for this piece I composed like all of the electronic music, and then I had a collaborator come in my friend Ittai Korman, who’s credited in the film at the end. And together, we can post a bassline and he kind of took the lead on that and it came out so beautiful. Just having that natural, acoustic bass accompanying the kind of arpeggiation of the synths.

How about the foley effects involved. What was your process there?

I do a combination of things. I have a field recorder that I take around and get audio from cars, or, you know, wherever I’ll go to do forest and get water rushing, or I’ll go to 15-501 and get a ton of cars. For this project. I did a combination of recording and lifting sound effects from sound libraries. So then it sounds like foley, but it’s just like sound effects cut up.

It’s interesting that you were in this sort of desert-y like region, but what you see in the film is temperate forests. What made you want to show that environment even though you were in this other one?

Well, I mean, you got to make what you want to see. And I I grew up in the Northeast. I live in North Carolina now and I just love the green moist temperate forests. You got to create what you want to see in the world, right?

What is the main takeaway you’d like audiences to leave this film with?

I mean, I think the feeling that I convey in like, the kind of the climax of the film is like extreme stress and chaos. I guess anxiety is a part of that. But I kind of when I hear anxiety, I think about, you know, scheduling anxiety, or social anxiety or things that are total, totally, like you have thoughts about the anxiety in your brain. And what I’m trying to convey to this film is like, of course, physiological things lead to thoughts and feelings. But I wanted to convey more like the physiological stress that is caused by excessive sound pollution. And that, like, you know, our ears, and the structures in our brains associated with hearing evolved to alert us to danger and like, the structures that are associated with hearing are very closely tied with fear response areas of your brain. So when we hear a lot more noise than we’re used to, it makes us stressed and scared. So that’s what I was trying to convey.

How does this film fit into your catalog overall?

Yeah, I think I have a through line in all of my work about connecting to the natural world, and how we have so many of our best happiest moments outside, but we spend so little of our lives outside. Also, connection to nature was, like, a huge part of people’s lives pre-capitalism. And I won’t really get into that, but part of the belief systems that allowed people to be close to nature, you know, animistic beliefs about nature and the natural world and cultures that you know, magical cultures were deeply discouraged by the state between the transition from feudalism to capitalism, in Europe. So I feel like regaining a connection to nature is one way to perhaps mitigate a lot of the climate destruction, just like feeling close to the world. And so a lot of my work has to do with that.