Excerpted from the author’s 2021 honors thesis

From Hurdanos to Hakua Cults: On Ethnographic Surrealism in Buñuel and Rouch Films

Macy Meyer

Why doesn’t the documentary crew intervene to help suffering subjects in Las Hurdes?

Surrealism has never been a tradition or genre confined to a singular set of conventions, ideas or aesthetics. Surrealism is less a rigid system of ideology and more a wavering, fluid practice of liberation. Surrealism’s definition is often as elusive as the films that make use of it. André Breton, through his many writings on surrealism and especially in his Manifestos of Surrealism, has described it as an “activity” of the unconscious mind, or an encounter that is brought unto us through experiences free from the “reign of logic” (Breton 6). Breton wrote that surrealism was a revolutionary movement that sought to overthrow the oppressiveness of rational logic that led to destruction and murder such as World War I. Breton and the surrealists instead hailed the “superior reality” of the subconscious mind, resulting in the main tenets of the movement to include psychic automatism, dreamscapes and explorations of the working mind. Surrealism was a fight against rationality and reason to favor visions and aesthetics that depicted the irrational, the strange, the unexpected, the uncanny and the unconventional. Not only was surrealism an “intermedial” movement that spanned mediums from fine arts to film, but surrealism is also what can be called “intergeneric” (Warner). Surrealism is an artistic movement that is not restricted to specific conventions or aesthetics, and therefore, surrealist filmmakers used surrealism as a mode or aspect of their films across genres. There is no limit to where surrealism can be used within the film medium. Surrealism can be found in melodramas, comedies, horror films, romances, any mainstream genre, and, most critically for my purposes, documentary.

In this essay, I will focus on the intersection of surrealism with the documentary genre, specifically analyzing the surrealists’ particular inclination to engage in ethnographic activity in those surreal documentaries. In the early to mid-1900s, a number of the key figures associated with surrealism sought to explore the customs, practices or phenomena of other, often exotic, peoples and cultures to tap into a new reality. It has been stated that surrealists were motivated by the need to liberate thought, language, and human experience from the oppressive boundaries of rationalism, and one method was to free themselves from the normality of their own culture to explore another in a cultural awakening. In his seminal essay “On Ethnographic Surrealism,” James Clifford describes this new phenomenon as a particular research perspective that intersected both anthropologists and artists in the two decades following the end of the First World War (539). He provides the earliest definition of ethnographic surrealism as those works that “attacks the familiar, provoking the irruption of otherness – the unexpected” (562). In this way, we can understand this particular surrealist activity as a turn away from the bizarre of the subconscious, to a study of the bizarre and strange of the monotonous day-to-day events in an unfamiliar culture and landscape. This essay will specifically analyze Luis Buñuel’s Las Hurdes: Tierra Sin Pan (Land Without Bread, 1933) and Jean Rouch’s Les Maitres Fous (The Mad Masters, 1955) to explore the particular way surrealists used anthropology or anthropologists used the mode of surrealism to create strange, and often, troubling documents of life in other cultures. I will argue in this paper that surrealism, and the particular activity of undercutting realism with surrealism when the viewer least expects it, is what makes it possible to deeply explore otherness. By applying the mode of surrealism to the ethnographic practice, filmmakers are able to use these contradictory forms to produce an aggressive experiential reality, which often conveys important socio-political commentary. I will then make the case that these films whose agendas are to shock and disturb us are absolutely necessary historically and socially critical tools for fixing the suffering depicted in the films.

It can often be difficult to comprehend the nature of Buñuel’s surrealist documentary, pinpointing how it is both surreal and seemingly objective documentation. Mercé Ibarz in “A Serious Experiment: Land Without Bread, 1933″ provides a working definition. She describes it as “a multi-layered and unnerving use of sound, the juxtaposition of narrative forms already learnt from the written press, travelogues and new pedagogic methods, as well as through a subversive use of photographed and filmed documents understood as a basis for contemporary propaganda for the masses” (Ibarz 28). Buñuel was able to create an amalgamated genre that combined both surrealist aesthetics, leftist politics and documentary traditions where the hybridity formed a staunchly unsettling and provocative experimental reality. Buñuel’s Las Hurdes works as a mockumentary, combining objective documentation of a rural Spanish community and a parody of such documentary conventions. The film is not entirely fabricated, as Buñuel creates a 27 minute portrait of life as a Hurdano, but the film sits at the crossroads of objectivity and partiality. Las Hurdes expands upon the many disjunctive cinematic conventions of Buñuel’s canonical surreal films – such as blurring the boundaries of both the real and the surreal, upsetting narrative continuity and distorting the coherence of space and time – and includes the guiding anti-capitalist and anti-bourgeoisie ideals of the surrealism group. Indeed, this film is very much still indebted to Buñuel’s deep roots with both the surrealist aesthetics and social stances of the movement. But perhaps the most peculiar aspect of Buñuel’s film – and what makes it decidedly ethnographic surrealism instead of just a bizarre, experimental documentary – is the filmmaker’s constant undercutting of realism when the spectator least expects it. This activity is what Clifford means when he argues that an ethnographic surrealist practice “attacks the familiar, provoking the irruption of otherness — the unexpected” (Clifford 562). In this case, Buñuel defamiliarizes the documentary genre and challenges its claims of truthful objectivity, but also lays an attack. Surrealism is key to this assault on documentary conventions in large part by the filmmaker’s incorporation of shocking images that attack the eyes of the spectator. Through violence, cruelty and otherwise disturbing imagery that was so common in surrealist works, these films make use of shock as a means of upending our sense of normalcy, of comfortable realism. Nowhere is this shock tactic more prominent than the famous goat scene.

The scene begins with shots of mountain goats climbing on and navigating through the sharp rocks of the Spanish mountains. In a series of shots, we see a pack of goats strategically making their way across the precarious slopes of the steep incline. The voiceover begins a long discussion of the importance of such goats to the town that suffers from a lack of resources. The goat’s milk is so crucial that it is given to the gravely ill and the townspeople refuse to kill the goats to eat their meat, and will only do so if one has died from falling or natural causes. Just as the narrator speaks these lines, the medium shot of the goat jumping over rocks cuts to a long shot of the goat falling down the mountain. The film then cuts to an aerial shot of the animal toppling and turning as it falls to its imminent death. These shots are crucial not only because the two perspectives of the goat falling imply that this scene was both staged and perhaps even repeated from multiple angles, but also because the long shot of the goat first falling allows us to see a puff of smoke in the center right of the frame, fading into the off-screen. It becomes clear from this puff of smoke that the goat was shot and intentionally killed. This point becomes even more fascinating when reading about the film’s production and finding that it was Buñuel himself who killed the goat for this scene. This participation on behalf of the filmmaker completely subverts the idea of objective documentation as Buñuel manipulated the scene, but it also forces the spectator to question the filmmaker; we have to ask why Buñuel would participate in such a cruel act against a creature so crucial to the town he is supposed trying to help by documenting their needs. His participation and the use of off-screen space cues the viewer to think about what is occurring off-screen, about the meaning beyond what is shown through the film image. Indeed, throughout the film it appears that Buñuel is much more concerned with mocking the Hurdanos’ lifestyle and lack of resources, but a deeper understanding of the film can allow the spectator to distinguish between what Buñuel is implicitly doing through irony and what the seeming authorial discourse, as voiced by the narrator, is doing. Buñuel’s authorship and participation in this scene signal that there is a subterranean layer of implied commentary from the filmmaker that does not quite match with the attitudes embodied by the narrator and the film’s agenda of callous condescension. There are numerous occasions where the Hurdanos themselves are compared to beasts to create a theme of dehumanization, which James Lastra suggests is thematic of ethnographic inscription. Lastra writes that Buñuel’s inclusion of a critical narrator and participation in violent scenes such as the goat killing, “serves to undermine the film’s claims to objectivity, the validity of ethnographic stagings more generally, and, most importantly, our own certainty about where the film stands, morally and politically” (Lastra 186). An ethical conundrum results to force us to reevaluate the film’s and Buñuel’s own attitudes towards the Hurdanos. We must not mistake the filmmaker’s participation as an opportunity for Buñuel to enforce his derision towards the Hurdanos, but as his deliberate subversion of the promised transparency of the film to atone for the inhumanity shown to the Hudanos. It is a “mea culpa” that stresses Buñuel is in fact not just aware of the film’s insensitivity, but is actively making it such to criticize his own film (Lastra 186).

Outside of Buñuel’s film, few scholars have conducted serious research about the surreal ethnographic films that came after, the films that continued and expanded the legacy of Las Hurdes. The post-World War II period in France still had strong inclinations towards surrealism as a mode in filmmaking. Michael Richardson has even suggested, in his essay “Surrealism and Documentary,” that the documentary tradition was so marked by surrealism that it became “its dominant influence during the early fifties” (87). Of this time period, one figure who stands out as sitting right at the crossroads of surrealism and ethnographic documentary is Jean Rouch. As one of the most significant ethnographic filmmakers of his time with films such as Chronicle of a Summer (1961) and Moi, Un Noir (1958), Rouch’s filmmaking style was predominantly much more realist in nature and belonging to documentary compared to Buñuel, but he also worked with the surrealism mode more decidedly than his peers. As an interesting paradox, his non-fiction filmmaking tended to incorporate surrealism, though he was never decidedly a Surrealist and many overlook his surrealist tendencies.

Nowhere are his surrealist tendencies more evident than his notorious film, Les Maitres Fous. This film not only stands out as a strikingly surreal documentary, but it also brought him international attention and fame, though the attention was far from complimentary. Rouch, much like Buñuel, came under scrutiny for his apparent insensitive depiction of African culture and tradition. This thirty-six minute short film depicts a possession ritual of the Hakua cult of the Songhay and Zerma peoples in what was the African Gold Coast under British colonial rule (Richardson 89). Rouch provides an intimate account of this rare ritual. Not only was he personally invited by the group to record their cultural practice, but he also provides a close-up documentation of men and women becoming possessed by spirits, which was revolutionary for post-war audiences and contemporary audiences as Rouch was able to access such an event as well as expose global audiences to it. It is notable that the Hakua cult emerged from Niger in the early twenties, likely as a result of trauma from colonial occupation (Richardson 89). This colonial history will not only be relevant to the action of the film, but it stands in solidarity with the anti-colonialist stance of the surrealists who saw the colonial empires of France and Britain mobilize in the post-war period and their predecessors who were witness to the wrecked nations left after decolonization.

Rouch’s film makes use of the same ethnographic surrealist tradition described by Clifford – to paraphrase, Rouch subverts the predominant realism of the film with the extraordinary and supernatural ritual, inserting otherness and the “unexpected” at the forefront of the film (Clifford 562). He does so by bookending a cult-wide possession – in which its members are possessed by the dead, frothing from the mouth and engaging in activities that are challenging for spectators to witness – with scenes showcasing the banality, the normalcy of the villagers immediately before and after the ritual. It is important here to discern where surreal aesthetics are operating in Rouch’s film. The film is evidently bizarre and challenges the power of the ruling bourgeoisie, but it can be argued that the subject matter itself, the actual inclination to document and bear witness to a possession, is a surreal activity in itself. Jeanette DeBouzek writes in her essay “Jean Rouch’s ‘Ethnographie Surrealism’” that Rouch’s desire to document people in a trance “is the manifestation of a broader ‘surrealist’ interest in the world of the imagination, a world that was being explored by the poets — and the ethnographers — of the avant-garde of his youth” (DeBouzek 307). There is something inherently surreal about Rouch’s need to document an event so unusual to most of the world outside of that jungle.

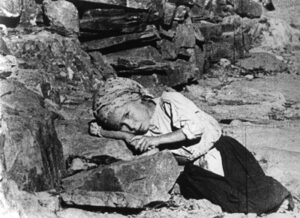

A shocking possession ritual in process in Les Maitres Fou

In what are perhaps the most striking scenes of the film, the Hakuas gather in the jungle with the intent to purge themselves of their everyday misfortunes through the possession ritual. They are especially optimistic that the ritual will cleanse them of their oppression as a colonized society. As the ceremony begins, the group slowly and subtly starts to act strange. The people seem to succumb to a manic spell. As the group begins to twitch and behave abnormally, the film’s style of presentation becomes increasingly frantic, with quick cuts and a shaky handheld camera. The camera seems to become possessed too, and mirrors the exorcist-like shaking of the ritual participants. Due to the disjunctive camera, along with the erratic diegetic soundscape that consists of an overlapping of tribal chants and ceremonial voices, the spectator becomes increasingly aware that they are witnessing a paranormal event, a truly surreal encounter of people becoming possessed. The ritual becomes increasingly more violent and unsettling, forcing the spectator to choose between looking away or continuing to see what they have never seen before. Rouch continues to operate with the surrealistic usage of shock images and bombards us with disturbing images: bodies convulsing and twisting in abnormal positions, Hakuas foaming at the mouth, a butchered dog, and human flesh blistering as it is exposed to fire and boiling water. The sequence is viscerally disturbing as we see the people subjugate themselves to these painful activities. While this is occurring, the voiceover tells the viewers that not only are the Hakuas being possessed, but they are possessed by colonialist spirits: generals and officials part of British colonialism in Africa are being mocked through the Hakua’s grotesque behavior that characterizes the colonists as barbaric. Not only do the carnal images shock and completely undercut the normalcy established at the opening of the film, but the gates are opened for socio-political commentary about the deep trauma inflicted by colonial occupation.

When Rouch’s film was first shown, there was immediate condemnation by both the colonial British authorities and many across the African academic sector. The film was banned across Niger and other British territories for its supposed racist depictions of the Hakua tribe. Like Buñuel’s film, Rouch offended everyone. Africans were upset at the depictions that showed their culture as savage, and the British authorities were furious at the mockery of their position. But also like Buñuel’s film, Les Maitres Fous should not be taken at face value. In fact, it is not a mindless, offensive depiction of an exotic culture; it is a crucial political commentary on the trauma and pain caused by colonialism. The ceremony becomes a parody of colonial occupation much like Las Hurdes’ mocking of a colonial gaze that makes a spectacle of exotic groups so often seen in travelogue films. The viewer is witness to the Hakua’s ecstasy post-possession when they see the ritual participants back in their daily routines and smiling at the camera. But this return to normalcy is upended as the viewer also leaves with a lingering disturbed feeling because they have just bore witness to the horrid violence and misery forced upon them by the colonial rule.

Both filmmakers strategically challenge the comfortable, the status quo and the familiar by using surrealism as a weapon in undercutting the familiar as it suits them. In doing so, they not only break down the trust in documentary as a genre that often promotes objective reality and attempts rhetorical persuasion, but they also challenge the spectator to see beyond the basic narrative, to work for the deeply meaningful messages hidden under the top layer. By undercutting the standard filmic conventions of documentaries and travelogues that often make viewers comfortable, Buñuel and Rouch force the audience to confront images that are difficult, painful, and often very confusing. By challenging the spectator’s comfort, the film removes any safety barriers so that what we expect of a documentary are reduced to ash and in turn, an entirely new perspective of the film can arise, forcing us to acknowledge the deep social and political commentary buried within the cracks.

It is important to note that Buñuel and Rouch carry out this breaking down of objectivity through different methods. Though both filmmakers are brazenly participatory with the filmmaker partaking in the events seen onscreen, Buñuel’s play with objectivity is much more difficult to spot. In Buñuel’s film, slight winks and nods to the spectator can be caught with a viewer knowing of the filmmaker’s larger surreal project and one that is keen to comedic irony, but anything less than full attention may lead us to believe he is nothing but an insensitive tyrant. Instead of laying all his cards on the table, Buñuel plays with the film’s objectivity by having the narrator promise transparency and truth from the outset and eventually breaks down any impartiality to reveal the cruelty of Western Europe’s colonial history. Rouch does the opposite. Rouch gives no pretense of objectivity; he has a crystalline anti-colonial stance when he shows the ecstasy of the ritual and the cruel influence of colonialism to lead such a group to purge in such a way.

As mentioned, both filmmakers faced intense derision post-release of each respective film. Banning and censorship prevented many contemporary audiences from experiencing the attack on their complacency with the bourgeoisie, authoritarian forces that brought forth the suffering depicted within each film. I argue that many audiences, both in the early to mid-1900s and now, are often unwilling and unable to challenge themselves by handling the provocative dimension brought to the surface by such films. Audiences are much more willing to sit through what makes them comfortable and secure, than confront their own behaviors that create negative aspects in the world. If suffering is shown on screen, we want to see no beauty in it and have the filmmaker clearly in good moral standing, but we also want to feel like the suffering is far removed from us personally and that we absolutely had no hand in causing it. Audiences want artists to play it safe, not challenge our own security while we are in a comfortable stasis while film watching. However, discomfort and shock are intrinsic aspects of Surrealism. From the very inception of the movement, Surrealism as a mode dedicated to the irrational and shocking lent itself to be a perfect conduit for revolting against society and stimulating a cultural reawakening. Surrealism goes hand in hand with rebellion, and as such seems to be an ideal mechanism for pushing the sharply political agenda of films like Rouch’s and Buñuel’s in which the filmmakers rebel against the ruling institutions and colonial attitudes. Though surrealism is often associated with dreamscapes and the fantasy across mediums, it is an apt tool in documentary films for its praxis of shocking viewers; shock often being a key mechanism for inciting socio-political action. From this, I argue that films such as Buñuel and Rouch’s are not just needed, but absolutely necessary. Using surrealism to produce provocative documentaries as a tool for activism or social critique is no doubt a lost activity, but an important one as our media landscape is saturated with that which makes us feel safe from the horrors of reality. Perhaps the legacy of such films has not been fully realized by modern documentarians, and perhaps it should be in order to awaken viewers to the horrors that are happening here and now.

Works Cited

Breton, André. “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Manifestoes of Surrealism. The University of Michigan Press, 1969.

Clifford, James. “On Ethnographic Surrealism.” Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 23, no. 4, 1981, pp. 539–564. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/178393.

DeBouzek, Jeanette. “The ‘Ethnographic Surrealism’ of Jean Rouch.” Visual Anthropology. 2:3-4, 301-315,1989. DOI: 10.1080/08949468.1989.9966515.

Ibarz, Mercé. “A Serious Experiment: Land Without Bread, 1933.” Archivos de la filmoteca: Revista de estudios historicos sobre la imagen, 34: 21–25.

Lastra, James. “Why Is This Absurd Picture Here? Ethnology/Heterology/Buñuel”. Rites of Realism: Essays on Corporeal Cinema, edited by Ivone Margulies, Duke University Press, 2003.

Richardson, Michael. “Surrealism and the Documentary.” Surrealism and Cinema. Berg, New York, 2006.

Warner, Rick. “Approaching Cinematic Surrealism.” Surrealism and Cinema course, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, January 12, 2021.