Cosmic Rays Film Festival 2020

Introduction by Josh Martin

Immediately prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, student writers for Aspect: Journal of Film and Screen Media had one last chance for a film festival experience, attending and screening films at the 2020 Cosmic Rays Film Festival. The fest, which was held from March 5-7, 2020 at the Varsity Theatre in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, showcased the best work in experimental cinema for the audiences of the Triangle area. With the 2021 edition of the festival canceled due to the continuing global pandemic — and the future of in-person film festivals in further peril — these reviews from the 2020 edition reinforce the essential work that these artistic events do for communities like Chapel Hill.

Even more crucially, these reviews highlight the continuing vibrancy of contemporary experimental cinema. Whether engaging with famous images, digital media, or household items, these films stretch the possibilities of the medium in challenging and fascinating ways. The first of two volumes of reviews from Cosmic Rays 2020 addresses films from Shelly Silver, Jodie Mack, Zachary Epcar, and Ross Meckfessel, ending with a dispatch from the festival’s wide-ranging celebration of the work of Naomi Uman. Read more from Aspect’s team of writers below!

Turn

By Josh Martin

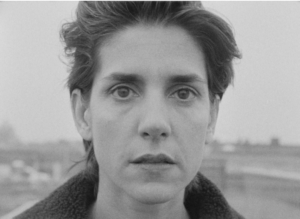

Photo Credit: Shelly Silver

Entirely silent and shot in pristine black-and-white, Shelly Silver’s Turn pushes the limits of our fascination with a single, seemingly insignificant movement. Inspired by the final image of Jean Seberg in Jean-Luc Godard’s iconic 1960 film Breathless, Turn displays a series of women turning around and meeting the gaze of the spectator (according to the festival guide, the film was shot in Berlin in 2017), changing the power dynamics of Seberg’s turn away from the camera. The diversity of the participants and their varied performances of this single gesture provide the most compelling aspects of the film. Some are young and some are old; some take the opportunity to smile, while others seem intent on maintaining a pensive, reserved expression. Though the various turns are arguably too short for the viewer to gain any real impression of the physiognomy of the performers, the film’s stated thesis – a homage/reinvention of a classic image that could reveal new political and emotional dimensions – gives it a curious power.

Wasteland No. 2

By Melissa Tomczak

Photo Credit: Jodie Mack

Jodie Mack called her first installment in the Wasteland series, Wasteland No. 1: Ardent, Verdant, a “eulogy for wasted potential.” It clashes the vastness of beauty in nature with the close details of technology as fields of bright red poppies flash between the intricacies of motherboards. Wasteland No. 2: Hardy, Hearty is not quite a continuation of the ideas presented in No. 1, but a regression into the origin of the relationship between nature and its mortality, and therefore its eventual interaction with technology. The leaves and flowers presented in Wasteland No. 2 are all cut from their stems, sitting on a sterile white surface or suspended in a melting gel-like substance. Roots, either dead or cut from their plant, dry up and flake onto the background. Much of the film flashes between these images, the soaked flowers and the dry roots they were torn from. Like Wasteland No. 1 before it, the longer you watch the images blip across the screen, the heavier their association with one another becomes. Though the flowers and leaves seem alive and beautiful still, they are connected to the dead roots by their mortality. In the synopsis of Wasteland No. 2, Mack quotes a passage from Felix Salten’s “Bambi: A life in the woods,” where one leaf whispers to another, “can it really be true, that others come to take our places when we’re gone and after them still others, and more and more?” Wasteland No. 2 gives those leaves a second life with both their conserved beauty and their immortalization in the film itself. It ushers in the next growth into spring by assuring the leaves of winter that they live on with the others that take their place.

Billy

By Kirsten Smith

Photo Credit: Zachary Epcar

Zachary Epcar’s Billy begins with the haunting image of a flame; meanwhile, unseen characters call the titular character’s name in an encouraging fashion that soon turns to despair. Soon, we see a woman as she goes to check on her roommate and they talk about the man’s nightmare. From this opening sequence, there are a multitude of shots featuring different items, ranging from an Amazon box to glass being shattered on the floor. The entirety of the film plays as a mystery, though its source material is within the soap opera genre. The mystery appears to revolve around the materialism of everyday life, hinted at as the soundtrack cuts when there are examples of mass commercialism and materialism featured on the screen. The film emphasizes its focus on the material through shots of scattered objects and scarce dialogue. There are also more literal moments such as when the male character chugs a bottle of imported water or the soundtrack of Melrose Place plays as the first-person perspective looks at a room filled with televisions and other luxury technological devices. The biggest indicator of the theme is found as the film ends in what appears to be an Amazon fulfillment center, with the man who looks to have delivered the initial Amazon package framed at the far end of the row. The film twists the overly melodramatic plot found in Melrose Place and turns it into a mysterious and subtle commentary on the problems found within the culture today.

The Air of the Earth in Your Lungs

By Josh Martin

Photo Credit: Ross Meckfessel

Ross Meckfessel’s The Air of the Earth in Your Lungs is described as “a landscape film for the 21st century,” focusing on the interaction between real, tangible environments and cinematic and virtual representations of that natural world. With Kanye West’s “Fade” and cacophonous bursts of piercing sound accompanying the dizzying visuals, Meckfessel plays a clever game with our perception of cinematic depictions of nature. The film presents the guise of the space of nature – trees, grass, even the presence of natural sounds – only to either slowly remind us of these images’ inherently false quality, or revealing a sudden interruption of the natural world by way of modern technology. The result is an assault on the senses, but this barrage of colorful manipulations and virtual spaces ultimately evokes and critiques a mode of constructed reality that is as immersive as it is purely simulated.