You Made Me Do This: On representation and identity in Friedkin’s Cruising

By Melissa Tomczak

Abstract:

William Friedkin’s 1980 Cruising takes place in a New York City that stopped existing only a couple years after the premiere of the film. A serial killer is targeting gay leather/S&M clubs in the meatpacking district, and officer Steve Burns (Al Pacino), matching the victim profile, is sent undercover to try and lure the killer out. During its production and upon its release, the film was protested and boycotted by the gay community. Its reception and its setting’s almost immediate fall from relevance due to the AIDS crisis resulted in a fade to the background of Friedkin and Pacino’s much talked-about careers. Currently, if anyone watches the film at all, the conversation is focused around its tumultuous production. Here, I try to answer if the film is actually as damning as its reputation makes it out to be. The film, both intentionally and not, is thematically confusing and a tangled web of doubling and exercises in subjectivity. I find that a large part of its confusion is a result of a struggle against adaptation, thematic abstraction, and the audience’s unwillingness to listen to exactly what the film is telling it. The film is more radical in its willingness to show depth in the gay community rather than making it more palatable to a heterosexual audience.

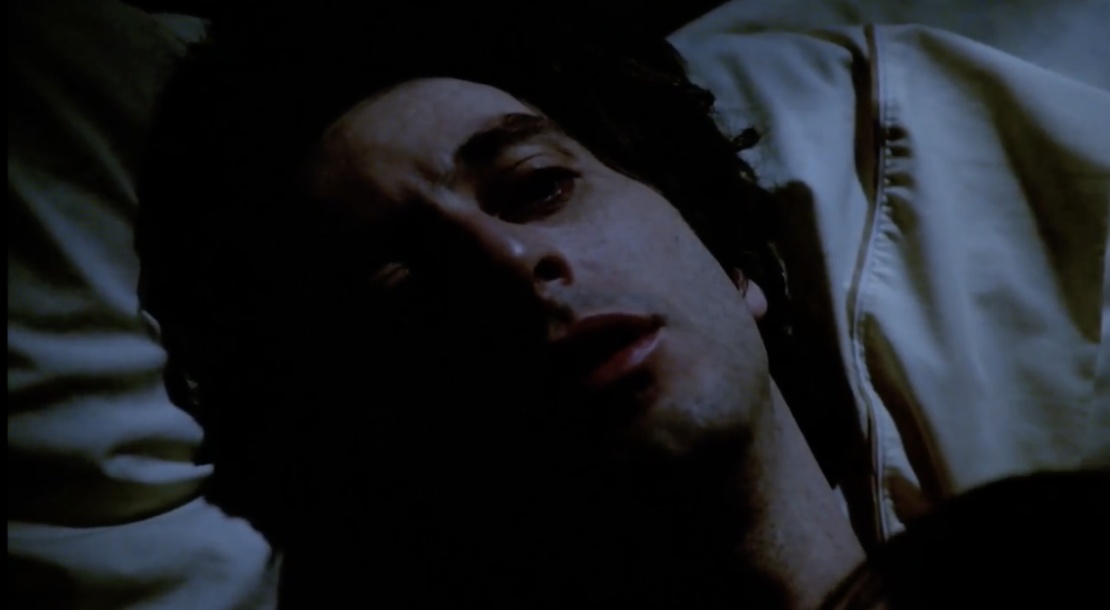

A week after watching William Friedkin’s 1980 film Cruising, I hadn’t stopped thinking about it. Whether it was the film’s striking imagery, ambiguous ending, or controversial production that sticks most in the mind, it’s safe to say anyone who has seen it did not soon forget it, either. Cruising centers around a series of murders targeting gay men in the leather S&M scene in New York City. Police officer Steve Burns (Al Pacino), who fits the victim profile, goes undercover in an attempt to draw out the killer and earn himself a detective title. As he goes deeper undercover, Burns struggles with his identity and potentially uncovers his repressed homosexuality. The film wouldn’t leave my mind partly because Al Pacino looks great in a leather jacket, but mostly because it’s one of the most thematically confusing films I’ve seen in recent memory. In part, I believe, by design partly as a result of a struggle against adaptation and thematic inconsistency.

Most commentary on Cruising now focuses on its tumultuous production, where members of the gay community disrupted shoots and called for boycots in the press. Friedkin was forced to cut more than 40 minutes from the film to secure an R rating. When Cruising is mentioned in contemporary media, it’s often to recall the negative press in 1980 rather than explore the film itself, and so over the years it’s been forced further into the background, now simply a dark spot on Pacino and Friedkin’s generally celebrated filmography. But few publications actually tackle what the resulting film communicates to the audience, both through the formal elements and more directly through the issue of representation. So, here, I will try to untangle the thread of logic that runs through Cruising and ask if the final product is actually as damning as its reputation.

The source material, the 1970 novel of the same name by Gerald Walker, isn’t quite as difficult to wrestle with as its adaptation. I found the book to be significantly more troubling than the film, with nearly unbearable characters and grotesque choices of depiction when it came to the gay community. Some of the same parallels that Walker arises in the novel appear in the film, but they take on a more subtle meaning without the internal monologue that is available in the novel. In the end, the differences between the two serve to highlight the nuances of representation and theme in the film. Friedkin has taken the plot of the novel and inserted those nuances where the book is lacking them.

The film follows certain elements of the novel precisely and completely departs in other major ways, one being the backdrop of the gay leather S&M scene, which was virtually nonexistent at the time the book was published in 1970. The important information one can glean from the novel in its service toward the film is twofold, and consists of the most significant elements of the film. First is the theme of doubling in nearly every aspect of its construction. Second, the difference in the characterization of the officer, John Lynch in the novel and Steve Burns in the film, assigned to the case. The character’s transformation from Lynch to Burns points toward Friedkin’s aforementioned insertion of nuance and even empathy where it did not exist in the novel.

The most prominent motif in Cruising is that of double meaning, repetition and parallel construction. In its clearest moments, this doubling establishes that the line between pursuer and pursued is blurred and even flipped, most commonly in the relationship between the police force and the murderer. In a film so concerned with identity and the loss of it, blurred boundaries of literal and figurative roles become vital.

The title itself holds double meaning, as the term for searching for a sexual partner or cruising in a police car. Burns is pretending to do the former and figuratively does the latter. There is further doubling of language in the terminology of the police department. Anton Bitel for Little White Lies wrote that there is a “complete slippage between the languages of police investigation and of homoerotic activity,” when Burns’ police captain Edelman (Paul Sorvino) says, “you fingered him” in reference to Burns suggesting a suspect. “I fingered him,” Burns replies, “but I didn’t think anyone was going to go that far with him.” Later in the same scene, Edelson says “we’re up to our ass in this,” when trying to convince Burns to stay on the case.

When Burns tells his girlfriend, Nancy (Karen Allen), and Edelman that the job is affecting him and he can’t deal with “what’s happening” to him, does he mean that repressed emotions are surfacing, or that violence is blooming inside him? These conflations of language, often with one foot in authority or violence of the police force, situates Burns deeper into the limbo territory he occupies as a cop realizing the flaws of his job and as a repressed gay man realizing his feelings for the first time.

There is the obvious notion of a “double life” as a gay man, in the closet or out. Repressed and unaware, like Burns, or out and comfortable, like the neighbor he befriends (and eventually develops feelings for) while undercover, Tim (Don Scardino). Steve Burns himself is a Russian nesting doll of doubles. The double life of the undercover detective is clearly meant to reflect the double life of the closeted gay man, and those tensions within Burns are conflated when he expresses that the job is changing him. Further, when the killer is revealed to be Stuart Richards (Richard Cox), a student at Columbia, we find he not only leads a double life but a triple or quadruple one. He is a straight graduate student, a self-hating gay man, a frequenter of leather/S&M clubs, and a serial killer.

Within that is also the equating of Burns and the killer. In the climax, when Burns lures Richards into Central Park, he imitates the killer’s own calling card of whistling and singing a children’s rhyme. He apprehends him the same way Richards kills his victims — leading with the promise of sex, then stabbing him. Burns is equated with Richards throughout the film, not just in the end. As critic Robin Wood points out, earlier in the film Burns returns to his apartment directly after a stabbing in the peep show looking worn out and disturbed, though we haven’t been privy to any of his actions from that night. By the end, it could be interpreted that Burns has taken Richards’ place. This is part of a continued motif where the predator becomes the prey. Richards, normally the predator, becomes Burns’ prey. Burns is in pursuit of a killer, but in order to do that he must put himself in the position of the hunted. If someone cruising for sex is hunting for it, they too become the hunted when they fall victim to the serial killer.

To magnify this conflation of predator and prey, Friedkin switches the actors who play the killer in nearly every scene until his identity is revealed. The actor who portrays him in the opening murder scene, Larry Atlas, becomes the victim in the next. The third murder features yet another actor as the killer, so by the time the actual killer is revealed, there is no satisfaction because there is no recognition and, therefore, no certainty. Just as Burns is confused in his identity, that uncertainty is carried through the rest of the film. Wood writes that the result of all this confusion is that “everything becomes a matter of ‘if,’ ‘maybe,’ ‘let’s pretend’ rather than ‘this is what happened.’” Thus, digging the heels of the film further into the interior space of Burns’ identity crisis. One could walk in circles (and I have) about the logic of the film and what it suggests in the concrete narrative. But that’s not what Friedkin cares about, and it’s not what is important.

All of this confusion and switching of roles serves the theme of identity that Burns struggles with. And what better way to explore identity than to plunge a repressed character into a situation where they are confronted head on and violently with that repression. As Drew Fitzpatrick put it for Digital Destruction, “It might not be the most politically correct choice, but in this context, the gay community is the perfect setting for a film that deals with duality and loss of identity.”

Burns’ role as an undercover cop, of course, is the most blatant form of doubling presented on the screen, and is the basis for Burns’ crisis of identity. To best explore this duality, one must consider the change from novel to screen and how Friedkin’s transformation of the character informs how one reads the film.

Lynch, the Steve Burns equivalent in the novel, is cruel, hateful, and borderline psychopathic even before he starts killing. He suggests at one point that the police should allow the killer to keep murdering gay men in order to, as he says, “clean up the city” (a notion that, in its Travis Bickle-esque perversion, was likely not an uncommon sentiment during the murders that loosely inspired the story). Steve Burns, thanks greatly to Pacino’s gentle and deer-in-headlights performance, is sympathetic and goal-oriented, simply out of touch for the majority of the film. Friedkin strips away the elements of Lynch that make him revolting and saves the most compelling plot elements for Burns.

Burns is actively sympathetic towards the gay community in the film, stating outright that he doesn’t want to bring any harm to individuals or the community as a whole. When he experiences brutality at the hands of police that is targeted at gay men, his connection to the case as an officer begins to erode. Burns’ reaction to this brutalization is one of confusion and betrayal, of a man who thought cops are always there to protect — a belief that he spells out plainly when he states that “the cops will get [the killer],” with a flippancy only possible from a fellow cop. (The responding line is the best in the film — “Cops? If they get their hands on him, they’ll make him a member of the vice squad,” — and is unfortunately straight out of the novel.)

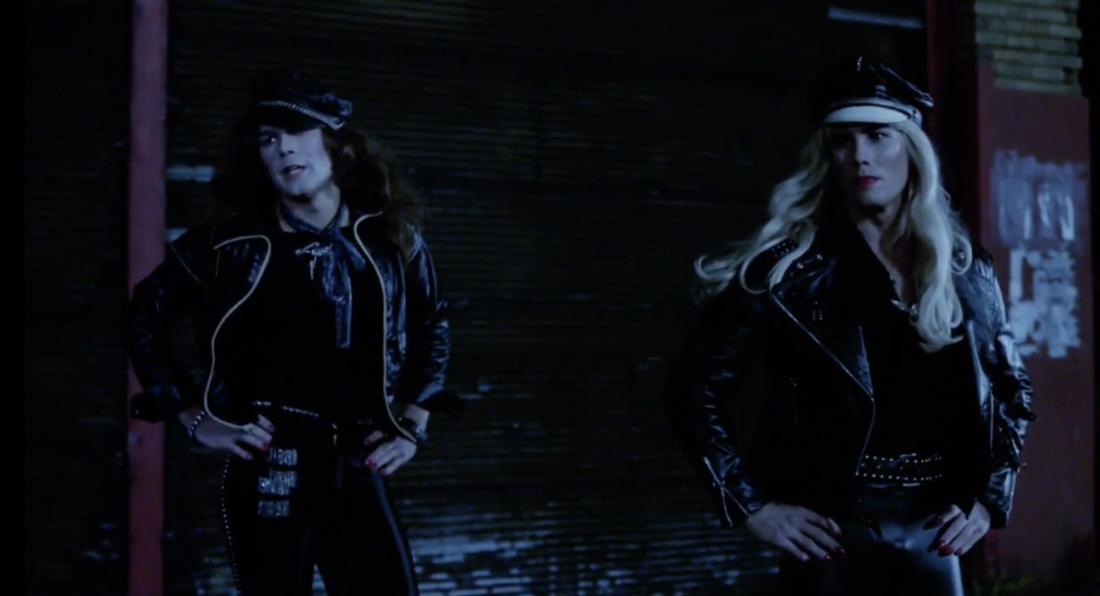

But this notion that cops always protect is never treated as a possibility by the film. Before Al Pacino even shows up on screen (15 minutes into the film), we are made familiar with the world that he is already part of and the one in which he is about to be inserted. The first scene has a detective, after a severed arm is found in the Hudson, telling the coroner to tag it “undetermined, pending police investigation,” a death knell for any hope of a case getting solved. The detective doesn’t care, citing that he has too much on his plate to deal with it. The very next scene narrows even further. Two cops stop two trans women about to enter a leather bar and force them to enter their cruiser and perform oral sex on them, all while insulting them. Before the officer approaches them, we see him following behind them in the same way we will later see the killer stalk his victims. One of the women is later revealed to be a frequent informant to the prescient, but despite their mutually beneficial relationship, Captain Edelman shrugs her off when she tries to report the officer who abused them. By the time Burns enters the film, the viewer is to fully understand the world he is stepping into and the one in which he’s already complacent. The fear from the gay community is equally distributed toward the cops and the killer.

As the film progresses, it seems Burns becomes more aware that the police force is aligned closer with the killer than the community they’re supposed to protect. When Burns is brought in with a suspect and they must interrogate him to keep appearances, he experiences first-hand the abuse dealt out by the police as they repeatedly slap and punch him and the clearly innocent suspect. As a consequence, he is stuck between a world that he thought he had no connection to in the gay community and a world he no longer trusts in the police force. The tension results in an internal struggle that grows tighter as his investigation progresses. That internal struggle, however, is where Friedkin’s cherry-picking of his characterization falters. His very attempt to improve upon the source material results in a character arc where its ambiguity is incongruous with the rest of the film.

The last five minutes of the film is the source of the confusion, and where Friedkin’s character alteration poses the biggest problem for the film’s coherence. After Burns apprehends the presumed killer, Captain Edelman assures Burns he will get off on necessary force. The ambiguity enters when Edelman is called into a murder scene that night: Tim, Burns’ neighbor during his time undercover, has been stabbed to death in his apartment. Upon the realization of their connection, Edelman mutters seemingly in a moment of realization, “Jesus Christ.” The last scene has Burns back in his girlfriend’s apartment, with no readable emotions the whole scene. While his girlfriend tries on the leather he’s been donning, Burns shaves and looks through the mirror into the lens and at the viewer. The image fades to a view of the East River that imitates the opening of the film, suggesting a return to the beginning and repetition of the film’s events.

And so there is doubling even in the film’s end that lies in audience interpretation. One could read the end in two basic ways: Burns has taken on the role of the killer and is responsible for Tim’s death, or Tim was killed by someone else and Burns is preparing to move on with his life with his girlfriend, now as a gold shield detective. The formal elements of the film could support either interpretation, but the problem is not in the ambiguity. It’s in the fact that an arc where Burns replaces the murderer and begins to kill gay men out of self-hatred is incongruous with his behavior in the rest of the film. Which is why the open ending could not be satisfying in relation to Burns’ character progression.

As mentioned earlier, Burns does not hate the gay community as Lynch, his equivalent in the novel, does. He is easy friends with Tim and doesn’t speak ill of the community. At his worst he is ignorant and struggles with culture shock. But as the film progresses, he is made aware of the troubles the gay community faces with the police and actually begins to have fun in the clubs. The only moment that shows Burns turning violent, inwards or otherwise, is when he gets angry at Tim’s boyfriend and tries to kick down his door. This, the only indication of violence, is not a logical progression from the rest of the film.

It becomes evident that Burns is realizing he’s gay, his experience undercover bringing up life-long repressed emotions. He tells Nancy and Captain Edelman that the job is “doing something” to him, and that it’s having an effect on him, though he doesn’t specify what that effect is. Depending on one’s interpretation of the end, this effect could be violence or realizing his repression. A troubling equivalency on Friedkin’s part to be sure, but again, few signs point him toward violence. The emotions toward his experience in the clubs and with Tim are more in line with confusion than anger.

I would argue that this thematic confusion in relation to character arc is a major reason that the rest of the film is cast in a negative light in regards to representation. If the newcomer to an environment is driven to murder, what does that imply about the environment? If Friedkin had not felt so tied to Lynch’s regression into murder in the novel, perhaps much of the negative interpretation could have been thwarted when it came to audience reception.

Deeper into the interpretation issue is the presentation of gay life, which many critics cited as the film’s largest issue of representation. Many detractors argued that the scenes among the gay leather clubs make it, especially through the eyes of the shocked Burns, appear dirty and sinister. But I would argue the opposite — while the representation of the leather scene isn’t palatable for all audiences, it doesn’t have to be. Fitzpatrick wrote that “the film is supposed to be seen through the eyes of ‘average Joe’ Steve Burns; it’s a shock for him, and needs to be a shock for us.” Melissa Anderson for Film Comment noted that when she saw Cruising as a young, closeted person, she thought, “This movie makes being gay seem scary. This movie makes being gay seem totally hot.” The club scenes are shot with flattering lighting, good music, and non-actors who were actual frequenters of the bars in which they filmed the scenes. As Wood put it, “How, if this is hell, do so many people appear to be enjoying themselves in it?”

Others argue that the scenes Burns shares with his girlfriend are comparatively bright and idyllic. While the club scenes may not be pictures of utopia, the idea that Nancy’s scenes are heavenly in contrast is simply not true. They’re shot with chiaroscuro lighting that is visually reminiscent of cut off and mutilated body parts, things that would plague Burns’ mind while they’re together. The repetitive music that plays in every scene with her is strangely eerie and devolves into an ambient clanging score at the tail end of one scene. Their conversations are strained and awkward. Even before Burns starts his undercover work, he comes across emotionally detached from her. In fact, as Fitzpatrick points out, the only scenes we see Burns make any real connection is with Ted. So this argument toward the framing of gay versus straight relationships falls flat.

Further, while some depictions of the gay, or more specifically leather/S&M, community as a whole may not be flattering (or accurate) to some, the individual gay characters are treated with nothing but empathy and humanity. With the exception of Tim’s boyfriend, gay characters are simply existing while trying to enjoy themselves among violence from police or the harsh stare of society as a whole. The two trans women from the opening scene are not only normal and sympathetic people, but the film aligns you with them to be frustrated with the cops that either abuse their authority or refuse to use that authority to help them. As Wood writes, there is no indication that we as the audience should be shocked by the mere existence of a gay person. That shock, again, comes from the culture shock through the eyes of Burns. The more damaging films, Wood continues, are those whose homophobia operates on a more covert and insidious basis. Cruising’s representation of gay life is too nuanced to be simply placed into the category of homophobic exploitation.

The demand of the protestors in 1979 and of current audiences boils down to wanting a softer, more appealing depiction of gay life. But it is depicted positively in the sense that it proves to be seductive, sexy, and mysterious. As Friedkin writes in the warning message in the opening of the film, it’s a portrayal of one community within the larger one, and a portrayal that the niche enthusiastically participated in at that. Just because that subset may be shocking to a larger straight or even gay audience does not mean it’s a negative one. Even if it were somehow showing an “ugly side” to a community, one should not be barred from showing it. While every representation of the gay community doesn’t have to, and shouldn’t, be like this, it doesn’t mean that it can’t exist and that it’s not equally productive. In fact, the film is more radical for this, demonstrating that there is more than one aspect to gay life, even if it’s not as palatable to the heterosexual world.

How you read the end of the film doesn’t matter. With all of its folding in on itself, the film practically begs the viewer to more carefully consider what they’re watching. The aforementioned final shot of the film, where we return to the New York City skyline from the East River, could be read as I described previously, with the implication that Burns will continue the self-hating murders. But Fitzpatrick touches on a more pointed reading of the end. Friedkin, with Burns’ look into our eyes and the repeated shot, is implicating the audience. We, like Burns, are sometimes the victim and sometimes the killer, and sometimes we find that we can be both.